In September, bunches of creamy white flowers adorn the heimang trees (Rhus chinensis) that grow widely across Manipur and the other northeastern states.

The flowers stand out against the green leaves of the deciduous tree, aptly earning them the nickname of ‘September beauty’. And by November and December, they transform into deep red cherry-like fruits with glandular velvety hair which have been used for centuries as food and medicine.

The spherical fruit has a citrus-like tartness and, though tiny, it is packed with nutrients such as polyphenols, flavonoids and antioxidants.

Traditional healers of Manipur, who are called the maibas or maibis, prescribe heimang for common gastro-intestinal problems like diarrhoea and dysentery. They recommend eating the water-soaked fruit for indigestion and stomach ulcer.

The healers say that the fruit is also useful in the treatment of kidney diseases and urinary stones.

Researchers with the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Central Food Technological Research Institute in Mysuru and the Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research at Ghaziabad support this claim.

Their study, conducted in vitro (experiments involving glassware, like test tubes), states that extracts of the heimang fruit inhibits the formation of calcium oxalate crystals (which make the most common type of kidney stones) and of experimentally induced urinary stones. The study was published in the Journal of Herbal Medicine in October 2021.

Other parts of the heimang tree such as its leaves (including the abnormal growths or galls on them), roots, stem and bark are also found to have preventive and therapeutic effects.

Apart from diarrhoea and dysentery, compounds derived from these tissues can be used in the treatment of ailments such as rectal and intestinal cancer, diabetes mellitus, sepsis, oral diseases and inflammation, states a review published in journal Phytotherapy Research in December 2010.

The plant has compounds that are good for the teeth as it prevents the enamel from losing minerals, researchers note in the review.

The 2010 review paper also finds that compounds isolated from the stem of the heimang tree can significantly suppress HIV-1 activity in vitro. HIV-1 is one of the two subtypes of the human immunodeficiency virus and is more widespread.

An August 2018 a review of 37 research articles published in the European Journal of Integrative Medicine also notes this benefit. It suggests heimang extracts may suppress HIV-1 and herpes simplex virus activity, reduce post-meal increase of blood glucose, prevent high cholesterol and protect the genetic material.

Local communities in the state also use heimang leaves to prepare a herbal shampoo called chinghi by boiling them with rice water. After cooling, the preparation is sieved using a muslin cloth and the clear liquid is used as shampoo. It can be stored for two to three days.

Researchers from the School of Food Science and Technology, Jiangnan University, China, have also tried to establish medicinal properties of the plant. They write in the March 2019 edition of journal Industrial Crops and Products that the oil produced from the fruit and seed has beneficial unsaturated fatty acids and phytochemicals and is a good ingredient to use in dietary food and nutrition supplements.

Manipur is part of one of the world’s most biodiverse areas, the Indo-Burma region, which spans the northeastern India and parts of other Southeast Asian countries.

Small wonder then, that heimang has a long history of culinary and medicinal use among communities in countries where the tree grows. In China, heimang is called yán fu mu; yán means salt in Mandarin.

In ancient China, certain communities used to add the fruit to food for its salty taste. It is still used by the Hani community that lives in the Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve.

The sour taste of the fruit, attributed to the presence of organic acids such as malic acid, citric acid and ascorbic acid, makes its use versatile. It is used to flavour meats, vegetables and even desserts.

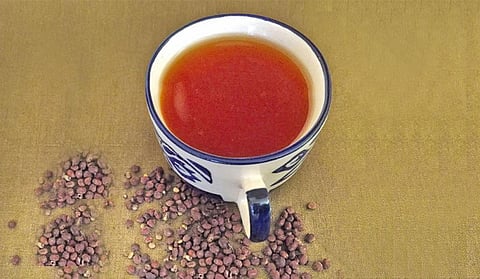

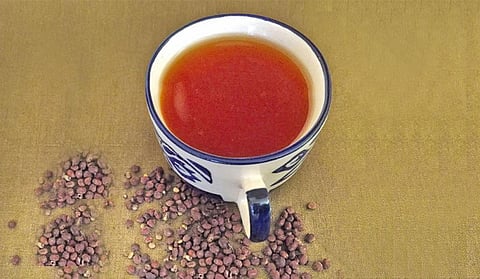

Traditionally, it is mixed with jaggery to make a nutritious and digestive candy. It is also dried and powdered to be used as a flavouring. Some simply boil the fruit in water and consume the decoction as herbal tea. To ensure year-round availability of the fruit for use in tea or as souring agents, fresh heimang fruits are dried and stored.

Despite its extraordinary versatility, heimang has not yet found widespread commercial use. Some companies in India have started including the fruit in herbal teabags. Promotion of such traditional products will provide livelihood opportunities for those communities that have access to the tree.

RECIPESHEIMANG TEA Ingredients Heimang fruits: 1 teaspoonTea leaves: 1/2 teaspoon Water: Enough for 2 cups of tea Sugar to taste Method Boil the water and add the tea leaves and heimang fruits. Sieve them out once the decoction is ready. You can also add ginger to the boiling water for enhanced taste and medicinal value, along with a pinch of salt. Add sugar as preferred and the tea is ready to be served.HEIMANG CHURAN Ingredients Heimang fruit: 100 gSugar: 10 g Salt to taste Method Dry and powder the heimang fruits. Blitz the sugar as well. Mix the powders with salt and the digestive churan is ready to be eaten on its own or sprinkled over salads. |

This was first published in the 1-15 January, 2023 print edition of Down To Earth