Book Excerpt: As bee populations continue to fall, we are heading for serious trouble

Photo: iStock

There you are, playing outdoors, kicking a football around, or simply lying back in the grass gazing at the clouds, when ‘Owww!’ you leap up with a shriek as something hums past your ears like a close-flying plane. You clutch your arm or leg or face, where you can see a small angry red spot begin to swell up. Yes, it’s a childhood rite of passage—to be stung by a bee (or worse, wasp). Back home you watch tearfully or stoically (as the case may be)

as a sterilized needle is used to remove the evil little stinger clinging tenaciously to your flesh. Every child has been, or should have been, stung at least once by a bee; though some children and adults really cannot take that risk because they can develop a life-threatening allergy to bee venom and

would need an immediate trip to the hospital.

But humans have been around bees and known about them since the times of the ancient Egyptians and Greeks and began ‘domesticating’ them for their delicious honey some 4500 years ago. We began robbing hives much before that: 15,000 years ago! Bees evolved from ferocious carnivorous wasp species about 160 million years ago side by side with flowering plants. It’s believed that some of these wasps may have preyed on insects which ate nectar, and which made them sweet and gave them energy, so some wasps decided that hey, why not cut out the insects altogether and go straight for the motherlode—nectar-filled flowers! And so, over time they became vegans—and bees.

Apart from merely consuming nectar (for carbohydrates) and pollen (for protein), bees used them in different forms to bring up their larvae and build their hives. Thus, they concocted honey, beeswax, bee bread, propolis (a kind of adhesive used to fill gaps in the hive) and royal jelly. The last is specially enhanced with nutrients and produced by ‘nurse’ bees, and are reserved for princess larvae which are being groomed to be queens, and for queens. (Some argue that royal jelly is fed to all larvae regardless of sex or status.) Many people believe that royal jelly has remarkable medicinal qualities but this has not been scientifically proven. The largest bee, a leaf-cutting species, measures almost 4 cm. The smallest, a stingless worker species, less

than 2 mm.

Of course, there’s no such thing as a free lunch and bees pay back flowering plants by pollinating them as they go from one bloom to another. A bee may visit over one thousand flowers a day! This is hugely important for us: it’s believed that one-third of all human food is pollinated by insects and mammals, the majority of it by bees. Some bees are specialists and will visit only a single species of flower and its closely related family members, and are called

monolectic. Others only visit a few flowering species or the flowering family it hails from, and are called, oligoleges. Most are generalists, or polylectic, collecting honey and pollen indiscriminately from all kinds of flowers. Bees are estimated to produce twice or thrice as much honey as they require. Apart from nectar collection, beekeepers actually rent out hives (a very profitable business) to farmers for their pollination services.

As bee populations continue to fall around the world due to various reasons like pollution, indiscriminate use of pesticides, attack by parasites, habitat destruction and global warming, we are heading for serious trouble. The phenomenon of ‘colony collapse’ when entire colonies die or vanish, has become a major cause of worry. And as usual, we’ve been greedy: not satisfied with the quantity of honey European honeybees produced, we cross-bred them with a ferocious species of African honeybees way back in the 1950s. Alas, the resulting Africanized honeybees turned out to be no better at nectar gathering as their European counterparts—but were manic! They had very short, incandescent tempers; they chased down their victims for miles and stung them to death. And in 1957, they escaped from Brazil and headed northwards. They’ve reached some of the southern regions of the United States, and have since caused havoc, swarming into downtown areas and suchlike just because perhaps some motorist rudely blew his horn at them! They’re still heading north—200 to 300 miles a year.

Bees in general are pretty well equipped to collect pollen: some, like bumblebees, are furry and fuzzy so that the pollen adheres to their hairy bodies, while others have special ‘carry bags’ attached to their legs, which they fill up with pollen. To defend themselves, they have stings, and many bees are brightly coloured to warn off predators.

Today, there are some 16,000 species of bees in the world found everywhere except of course in poor old Antarctica, of which as many as 90 per cent are solitary. These include our familiar shiny black carpenter bees that hum around flowers like little winged motors. They nest in holes in bamboo shafts, twigs, wooden poles and suchlike where the female lays a single egg and provisions it with pollen and seals it and then makes another. She never lives to see her babies.

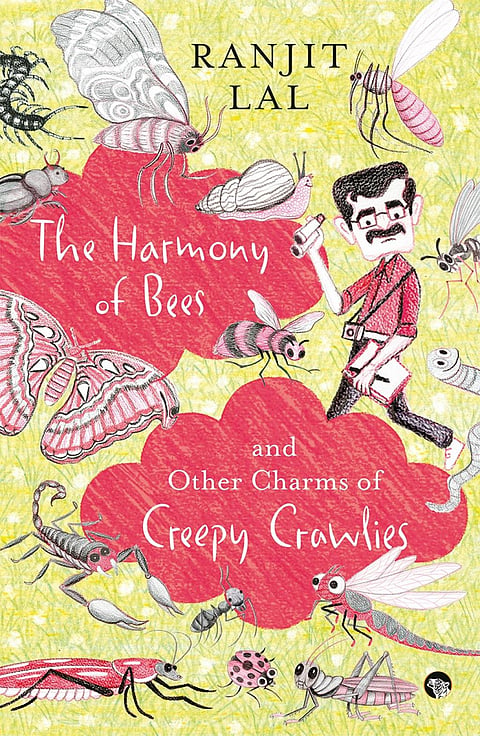

Excerpted with permission from The Harmony of Bees and Other Charms of Creepy Crawlies by Ranjit Lal Copyright @2023 by Talking Cub