Taking stock of the household use of packaging materials, a new research report has quantified the extent of plastic pollution caused by household consumption.

With the sale of 120 million plastic milk pouches on a daily basis, 8.68 billion servings of instant noodles on an annual basis, sale of 26.8 billion plastic detergent packets annually and the use of 3.3 billion cooking oil plastic packets, the research conducted by Delhi-based Chintan Environmental Research and Action Group has thrown light on the consumer behaviour behind this seemingly never-ending demand for plastics in India's FMCG sector.

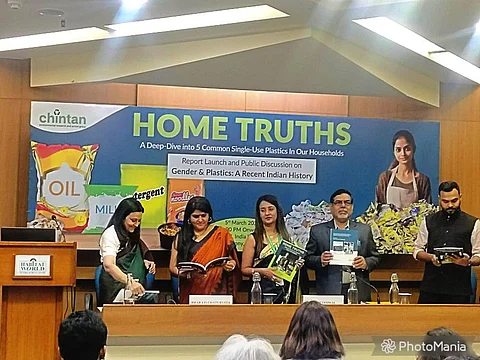

The report titled Home Truths — A Deep-Dive into 5 Common Single-Use Plastics in Our Household is authored by Nidhi Jamwal, Bharati Chaturvedi and Esha Lohia and edited by Pankaja Srinivasan. It not only addresses the exigencies arising out of plastic pollution but also provides a detailed assessment of public policy on plastic ever since its inception on a commercial scale.

In the report launch event held at Delhi's India Habitat Centre, a panel discussion was held on March 5 which on the use of common single use plastics in Indian households.

"Currently, 40 to 45 per cent of plastic globally is used for packaging, and plastics account for nearly 3.4 per cent of global emissions — a number expected to more than double by 2060. In a rapidly changing climate, we simply cannot afford this," Jamwal, an environment journalist and lead author of the report, said.

Meanwhile, Chaturvedi pointed out that science and global negotiations have made it clear that plastics are harmful for health.

"The real question is, what do we do now?" she asked.

The question resulted in a panel discussion in which it was observed that socio-cultural norms and changes have led to a spike in the usage of plastic products especially packaging materials.

Siddharth Ghanshyam Singh, programme manager of environmental governance and solid waste management at Centre for Science and Environment, shared an anecdote from his childhood as a 90s kid growing up in an India that had just embraced neo-liberal economic policies.

"In my childhood, I have seen my parents segregate plastic waste in our household. Old newspapers, milk packets, packaging materials, tin cans and oil containers were part of it. This waste was sold off to the local kabadiwallah (scrap dealer) who used to visit the house once in a month or so. The earnings from this waste was my pocket money," Singh shared.

He further explained that the old system in which kabadiwallah were an integral part of the waste disposal system for solid wastes in Indian households became redundant with time.

"By the time I was in my high school, I observed a sharp decline in my pocket money. The earnings from selling scrap lowered because the scrap dealer began refusing several scrap items. This was because these items were manufactured in a way that their recycling wouldn't yield any profits for the scrap dealer," he stated.

Meanwhile, Ram Niwas Jindal, former director in the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change remarked that while regulations prevent things like the sale of loose mustard oil due to adulteration concerns, we must take a broader perspective on our consumption choices.

"Addressing environmental challenges, particularly reducing single-use plastics, requires a balance between safety, sustainability, and responsible consumer actions," Jindal said.

The panelists also dwelled upon the idea of plastic neutrality and how it helps the polluting industries in finding caveats in governmental regulations.

"As this report shows, a number of companies have already declared, or are on the way of declaring themselves ‘plastic neutral’ despite the fact that plastic use in packaging of their products is on the rise," the report stated.

The research underlined that this self declaration needs to be cross checked and verified by independent third-party or credible government institutions.

It suggested that stakeholders need to think and assess if collecting plastic waste and sending it off to a waste-to-energy plant or a cement kiln qualifies as being ‘plastic neutral’.