The world knows the Inca Empire, the largest native polity in the Americas before the arrival of Europeans. But before it, there flourished another state, one of farmers, traders, fishers and diplomats. The secret of their economy and subsequent power was seabird guano, according to new research by the University of Sydney.

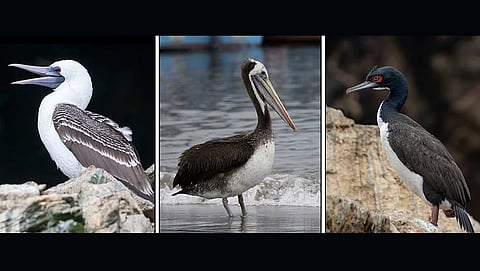

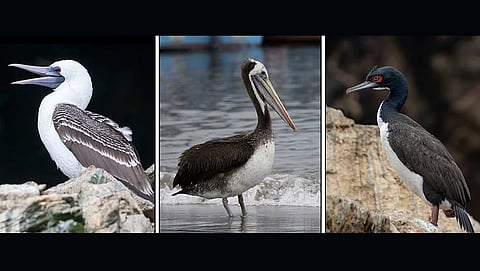

The droppings of birds found along the coastal desert near the Peruvian section of the Andes mountain range, were rich in nitrogen due to their diet which was rich in fish and other seafood.

The Chincha Indians, who resided in the nearby Chincha Valley, made all sorts of attempts to collect this guano. They then used it in their maize (corn) fields and gathered fabulous yields. This made them one of the most prosperous and influential pre‑Inca societies, according to a statement by the University.

“Seabird guano may seem trivial, yet our study suggests this potent resource could have significantly contributed to sociopolitical and economic change in the Peruvian Andes,” the statement quoted lead author Jacob Bongers as saying.

“Guano dramatically boosted the production of maize (corn), and this agricultural surplus crucially helped fuel the Chincha Kingdom’s economy, driving their trade, wealth, population growth and regional influence, and shaped their strategic alliance with the Inca Empire. In ancient Andean cultures, fertiliser was power,” he added.

The scientists analysed biochemical signatures in 35 maize samples recovered from burial tombs in the Chincha Valley, home to the kingdom populated by an estimated 100,000 people in its heyday.

They conducted chemical analyses which revealed exceptionally high nitrogen levels in the maize, far beyond the natural soil conditions typical for the area. “This strongly indicates the crops were fertilised with seabird guano, which is enriched in nitrogen due to the birds’ marine diets,” noted the statement.

According to Bongers, the guano was most likely harvested from the nearby Chincha Islands, renowned for their abundant and high-quality guano deposits. “Colonial‑era writings we studied report that communities across coastal Peru and northern Chile sailed to several nearby islands on rafts to collect seabird droppings for fertilisation.”

The researchers also examined regional archaeological imagery featuring seabirds, fish, and sprouting maize depicted together on textiles, ceramics, pottery, wall carvings and paintings, offering a further line of evidence that seabirds and maize held cultural importance in these ancient societies.

Bongers noted that so strong was the influence of guano in the area that people actively celebrated, protected and even ritualised the vital relationship between seabirds and agriculture.

Part of the reason as to why the residents recognised the exceptional power of this fertiliser was that farming on Peru’s coast is challenging, as it is one of the driest areas on Earth, where even irrigated soils quickly lose nutrients.

The Chincha though skillfully shipped poop from nearby islands, used it in their maize fields, and earned an agricultural surplus which enabled them to become major coastal traders.

So important was the poop as it helped growing maize that it was even used in diplomacy.

According to the statement, the Inca “were famously obsessed with maize, using it to make ceremonial fermented beer, or ‘chicha’. But they couldn’t grow much of it in their highland environments, nor could they sail”.

“Guano was a highly sought-after resource the Incas would have wanted access to, playing an important role in the diplomatic arrangements between the Inca and the Chincha communities,” Bongers said.

“It expanded Chincha’s agricultural productivity and mercantile influence, leading to exchanges of resources and power.”

Co-author Jo Osborn at Texas A&M University said the research invited us to reconsider what ‘wealth’ meant in the ancient Andes.

“The true power of the Chincha wasn’t just access to a resource; it was their mastery of a complex ecological system,” she said. “They possessed the traditional knowledge to see the connection between marine and terrestrial life, and they turned that knowledge into the agricultural surplus that built their kingdom. Their art celebrates this connection, showing us that their power was rooted in ecological wisdom, not just gold or silver.”

Seabirds shaped the expansion of pre-Inca society in Peru has been published in PLOS One.