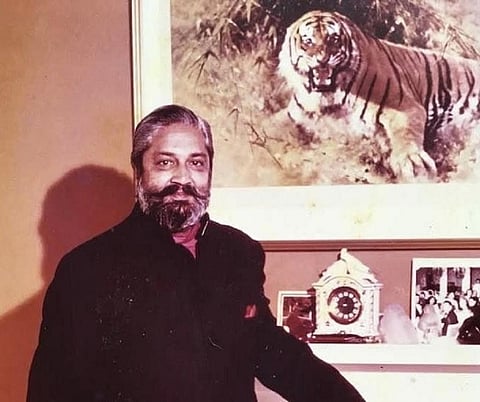

Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad, the royal environmentalist

Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad’s legacy is well known — he was a scion of a Maratha dynasty that dominated the politics of Gujarat for several centuries. The titular Maharaja of Baroda was the first Indian cricketer to be elected to Parliament and the youngest president of the Board of Control for Cricket in India. He contested four Lok Sabha elections — in 1957, 1962, 1971, and 1977 — and won all of them.

When the author asked Gaekwad’s neice, Priyadarshini Raje Scindia, to describe her uncle, she responded, “He was a caring person and children loved him.”

There isn’t widespread recognition of Gaekwad’s role in environmentalism.

He founded not only the World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-India, but also the Indian Society of Naturalists to combat the extinction of threatened plants and animals and the destruction of natural ecosystems. He made significant contributions to the development of India’s environmental movement.

Gaekwad’s great-grandfather, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, was among the most progressive and foresighted Maharajas. According to Smita Bhagwat and Avinash Captan’s book Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad: The Visionary, published by Matrubhumi Seva Trust, “He chose to improve the landscape by building many lavish public gardens and planting trees along the roads to give citizens relief from the hot climate.”

Sayajirao, in 1875, chose a plot of land on the banks of the Vishwamitri on the outskirts of Vadodara to establish a large garden and zoo. He donated his private collection of Indian and exotic animals to the zoo, and the park opened to the public on January 8, 1879.

Following in his great grandfather’s footsteps, Gaekwad established the Maharaja Fatehsingh Zoo, was closely involved in the establishment of the prestigious Delhi Zoological Gardens and chaired the Indian Board of Wildlife’s Expert Committee on Zoos.

He was instrumental in preserving Chennai’s lung space, better known as the Guindy deer park. The “beautiful deer sanctuary,” which was 555 acres in 1955, got reduced to 330 acres by 1973.

Congress leader Jairam Ramesh writes in his book Indira: A Life in Nature, “On November 24, Gaekwad, who was president of WWF-India, wrote to the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, urging him to secure the remaining 330 acres as a permanent deer sanctuary; this would, in his words, also act as a ‘lung to the fair city of Madras’. He sent a copy of the letter to the prime minister, pleading for her intervention.”

Staunch conservationist

The futility of hunting dawned upon Fatehsinghrao in Africa; from then on, he turned from a Shikari to a staunch conservationist. Tributes were heaped upon him for his work by several international organisations committed to environmentally sustainable development.

We find it mentioned in the magazine of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations, Tigerpaper (1982), “The credit for initiating conservation endeavours and a love for nature must go to the Vadodara Prince, Lt Col Fatehsinghrao P Gaekwad, a committed conservationist. It is no wonder that the paramount services rendered by Vadodara (Gaekwad), the President of WWF-India, have made wildlife a household word in Indian homes.”

When he passed away, Pat Foster-Turley, co-chairman of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Otter Specialist Group, wrote, “...we will always have his legacy, the initiation of otter conservation work in Asia. “Our Maharaja” has left us this gift of incalculable value, and it remains our task to realise its full worth.”

Foster-Turley gives credit to Fatehsinghrao for paving the way for organisation of International Otter Symposium in India — the first International Asian Otter Symposium, was held in Bangalore, India, from October 17-22, 1988.

She wrote, “At the 1985 fourth International Otter Symposium in Santa Cruz, California, Jackie (Gaekwad) proposed that the next meeting be held in India. For the ensuing three years, Jackie worked diligently to see this goal realised. He activated his impressive network of Indian government and conservation connections, who all pitched in wholeheartedly to make the conference a success.”

In India, according to botanist Gunwant M Oza, he played a prominent role in saving the Nilgiri Tahr (Hemitra-gus hylocrius) from extinction, implementing Project Tiger, founding the Wildlife Institute of India, saving the Silent Valley, protecting primates and influencing the decision-makers in enacting legislation such as Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 and Forest Conservation Act, 1980.

In 1985, Fatehsinghrao went to participate in the International Wildlife Film Festival at the University of Montana, where a dinner was organised in his honour. He was a well-known personality internationally committed to environmentalism and participated in several prominent events associated with the same.

Role in World Wildlife Fund

As the founder president of WWF-India, Gaekwad spearheaded its Bombay office and established its Gujarat office in Rajkot in 1975.

Oza wrote, “Soon after Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands became President of the World Wildlife Fund, he asked ‘Fateh’ to join its Board of International Trustees, on which the latter served for two 3-year’ terms. It was during his tenure of this international trusteeship that ‘Fateh’ set up the Indian National Appeal of WWF in 1969.”

The scope of WWF-India was enlarged in accordance with the organisation’s needs and the name changed to World Wide Fund for Nature-India.

WWF-India, which started as a one-man outfit, is now a huge organisation contributing significantly to the protection of wildlife in India. It played an integral role in the initiation of Project Tiger in the country and initiated the Community Biodiversity Conservation Movement between 1989 and 1991.

Several other important milestones in the journey of environmentalism in India were achieved thanks to the contribution of this organisation.

The Library & Documentation Centre, established in 1990 in the WWF-India Secretariat in New Delhi, has been named in Fatehsinghrao’s honour as Maharaja Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad Library & Documentation Centre and visitors can still see his bust here. This library houses over 17,000 volumes of books on a variety of subjects related to the environment and wildlife.

Gaekwad did inspirational work for protecting biodiversity and the movement of environmentalism he was a part of is expanding in India, thanks to the efforts of several environmentalists and nature lovers.

Arunansh B Goswami is head of Scindia Research Centre, Scindia Palace Gwalior.

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth