Researchers have found what they claim is the first physical evidence of combat between a gladiator and a large cat, probably a lion, in the Roman period.

The findings centre on a person’s bones from a Roman-period cemetery outside York in England. The site is believed to contain the remains of gladiators.

The bones of the individual showed distinct lesions that, upon close examination and comparison with modern zoological specimens, were identified as bite marks from a large feline species, a statement by Maynooth University, Ireland, noted.

“It is proposed, based on the evidence from the archaeological, medical and forensic evidence that the bite marks on 6DT19 derive from a large felid, such as a lion…The location solely on the pelvis suggests that they were not part of an attack per se, but rather the result of scavenging at around the time of death. The decapitation of this individual was likely either to put him out of his misery at the point of death, or for the sake of conforming to customary practice. Again, this is consistent with the literature,” according to the study.

“For years, our understanding of Roman gladiatorial combat and animal spectacles has relied heavily on historical texts and artistic depictions. This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region,” the statement quoted lead author Tim Thompson, Professor of Anthropology and Vice President for Students and Learning at Maynooth University.

The cemetery is located in Driffield Terrace, situated approximately a kilometre to the south west of York city centre.

York (Roman Eboracum) was founded as a fortress by the 9th Roman legion which was replaced by the 6th legion sometime before the year 120 AD and who were garrisoned there until the end of the Roman period in the early fifth century.

“Burial within settlements was forbidden in the Roman period, and the dead were, instead, often buried alongside the major roads leading to and from urban areas. Consistent with this, the Driffield Terrace burial ground is located along the major routeway between York and London, where it intersects with roads running from the west,” according to the study.

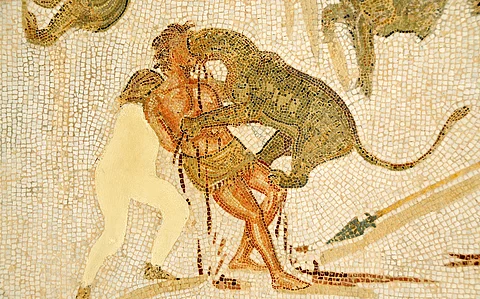

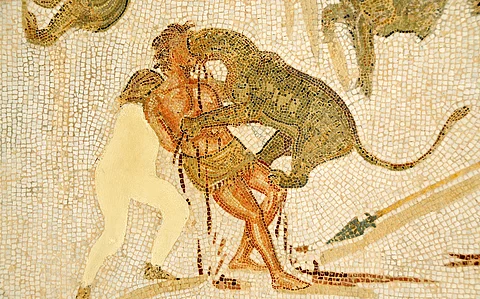

Roman amphitheatres also staged ‘beast hunts’ (venationes), which pitched people against animals, in addition to person-to-person combat.

“In these ‘beast hunts’, trained performers (‘venatores’) were armed and placed in an arena to ‘hunt’ large cats (including lions, tigers and leopards), bears, or large herbivores (including elephants and wild boar as well as stags and bulls). Animals were used, too, as the agents of spectacular mutilation and execution of criminals, captives from warfare and other perceived deviants, including Christians, who were also sometimes forced to participate in such events, known as ‘damnatio ad bestias’. These would sometimes include the re-enactment of mythical narratives as executions,” the study said.

According to the statement, the study contributes a vital new dimension to our knowledge of Roman Britain, reinforcing the region’s deep connection to the empire’s entertainment traditions. “These findings offer new avenues for research into the presence of exotic animals in Roman-period Britain and the lives of those involved in gladiatorial combat,” it said.

Unique osteological evidence for human-animal gladiatorial combat in Roman Britain has been published in the journal PLOS One.