An organism that hunted the dinosaurs, the crocodile (and its cousins like the alligator, caiman and gharial) has changed little in design from that time. It is this body design that has spelt immense survival success for this species.

Cultures across the world have idolised and deified the crocodile for it power, strength, ferocity and speed. From the makara in Hinduism and Buddhism and Sobek of the ancient Egyptians to the sacred beasts in the cultures of various indigenous American, sub-Saharan African and Australian Aboriginal and Papuan cultures, the crocodile has had huge impact on human culture, beliefs and faith systems.

One of the cultures that venerates the crocodile is part of the string of islands that stretch between Southeast Asia and Australia. They believe their island has itself been formed by the body of a crocodile.

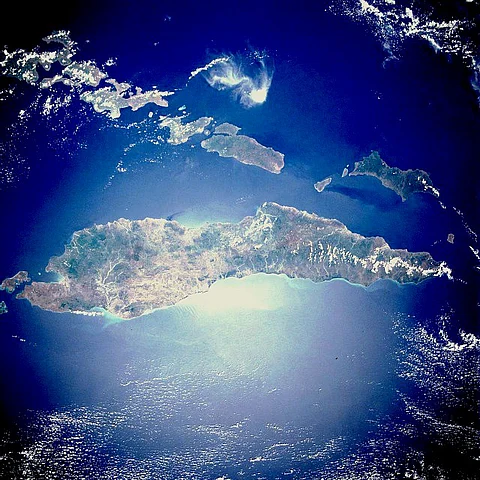

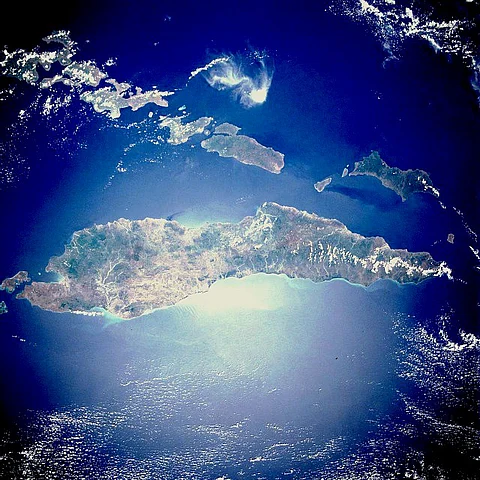

Timor is an island in the Indonesian archipelago. “Before colonization by the Portuguese and Dutch, Timor Island was fragmented into several small dominions ruled by executive rulers, the so-called Liurais. In 1515, Portuguese colonialists landed in Timor; in 1640 the island was separated into a westerly Dutch part and an easterly Portuguese part. Timor-Leste declared independence from Portugal in 1975, but was subsequently occupied by Indonesia, which initiated a 24-year period of occupation resisted by a guerrilla army led by the President (2002-2007) and Prime Minister (2007-2015) Xanana Gusmao. In 2002, independence was achieved after a three-year UN-led transition period,” Sebastian Brackhane, Josh Trindade, Grahame Webb and Peter Pechacek note in their 2019 paper titled Crocodile management in Timor-Leste: Drawing upon traditional ecological knowledge and cultural beliefs

So, what then connects Timor with crocodiles?

The Tetum people, indigenous inhabitants of Timor, have an enchanting legend.

They tell of a young boy, who once came across a baby crocodile trying to reach the sea from a lagoon. The boy took pity on the animal and helped him back to sea. The grateful crocodile promised to help the boy.

“The grateful crocodile promised the boy to help him and a few years later, the boy called the crocodile, by now fully grown, to travel the world on its back. After travelling the oceans for years, the crocodile told the boy that it soon had to die. “I will turn my body into a beautiful island for you and your descendants,” said the crocodile, and after it died, its body grew and today the ridged back of the crocodile forms the island of Timor,” Brackhane writes in Sharing a pond with Grandfather Crocodile (2024).

This, then, is the legend of Lafaek Diak (The Good Crocodile), which is the creation myth of the Timorese. It has led to an astonishing relationship between the people of the island and the saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus), which share it with them.

The saltwater or estuarine crocodile, which ranges from eastern India to northern Australia and the Solomon Islands, is the largest reptile on earth. It is also the most aggressive crocodilian, accounting for more human fatalities than the Nile crocodile, the Mugger crocodile, the American crocodile and the American alligator.

“The Timorese call their crocodiles ‘Avo Lafaek’ or Grandfather Crocodile…Crocodiles were hunted for their skin during the times of Portuguese colonisation and Indonesian occupation. The colonial times not only had an impact on the country’s saltwater crocodile population, but also on the spiritual life of the Timorese. Today, most Timorese are Catholics, after nearly 400 years of Portuguese colonisation and missionary work,” Brackhane notes in his 2024 article.

So important is the crocodile that the traditional Timorese belief system called lulik has a special place for it. “(Crocodiles) are part of the Timorese belief system lulik, which can be found among all ethnolinguistic groups of Timor-Leste. Lulik can be translated as ‘forbidden,’ ‘holy,’ or ‘sacred’ and “refers to the spiritual cosmos that contains the divine creator, the spirits of the ancestors, and the spiritual root of life, including sacred rules and regulations that dictate relationships between people and people and nature,” the 2019 paper notes.

Accordingly, crocodiles are so sacred that they cannot be hunted. Even more noteworthy is the fact that humans who become victims of crocodile attacks on Timor are often not even reported by relatives to authorities, who feel the attack has been a ‘punishment of the ancestors’.

The lulik system has managed to survive the 400-odd years of Portuguese and Dutch rule on Timor. In the eastern part of the island, in the country of Timor-Leste, it has even been integrated into Catholicism.

According to Brackhane, “…the Timorese simply integrated Catholicism into their lulik cosmology, without relinquishing their traditional, more animistic beliefs. Today, ceremonies for the grandfather crocodile can be conducted on a Saturday with the same people attending a Catholic liturgy the very next day.”

Research for the 2019 paper was conducted primarily in Timor-Leste. The authors noted in conclusion that “Extending attitudinal research to other communities and ethnicities, including Indonesian West Timor where similarly high rates of HCC (human crocodile conflict) and cultural affinities to crocodiles exist, could help ensure management is participatory and more effective.”