At 1.62°C above the pre-industrial level, November 2024 was the 16th of the last 17 months when global average surface air temperatures exceeded the warming limit of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This temperature rise does not mean that the world has crossed the guardrail of 1.5°C, which refers to a long-term average, but it does suggest that the window for limiting global warming to relatively safe levels is rapidly closing. The planet would continue to get hotter and the climate more dangerous unless countries raise commitments to reduce emissions in their latest nationally determined contributions (NDCs 3.0) that need to be updated by February 2025. NDCs 3.0, says the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, may be the last chance to put the world on track with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal, and must therefore reflect the plans of tripling global renewable power capacity and doubling energy efficiency by 2030, from the 2022 level, as agreed upon at the 28th UN climate summit (COP28) in 2023. The transition, however, will be an uphill task for developing countries like India in the absence of adequate international support like finance and technology transfer.

The latest NDC synthesis report says that the nations’ current climate plans “fall miles short of what’s needed” to achieve the 1.5°C scenario. Even if fully implemented, the current NDCs would see greenhouse gas emissions of 51.5 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2030—a level only 2.6 per cent lower than in 2019, it says, calling for bolder NDCs from every country.

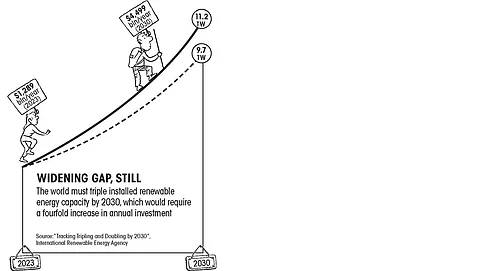

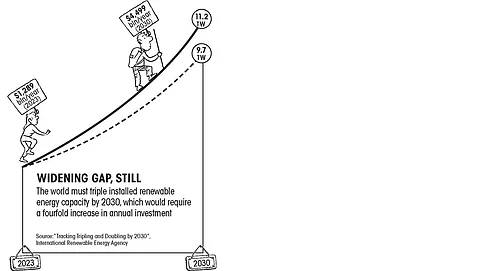

Tripling the renewable power capacity to achieve 11.2 terrawatts (TW) by 2030, above the 2022 levels, and doubling energy efficiency can be key milestones in achieving the goal. Current national plans and targets will deliver only half of the required growth by 2030, at 7.4 TW, resulting in a shortfall of 34 per cent in 2030. Of the three Parties that had submitted revised NDCs by the end of 2024, only one had enhanced ambitions for renewable energy targets.

Analysis by International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) shows tripling the capacity will require an average addition of 1,044 gigawatts a year from 2024 to 2030. For this, the world needs a cumulative investment of US $31.5 trillion. While annual investments in solar photovoltaic are on track to meet the $397 billion required each year until 2030, other technologies remain underfunded. Investment in energy efficiency improvement must increase sevenfold.

Renewables are set to become the dominant power generation source by 2038, with China, Europe and the US producing over 57 per cent of global solar and wind output by 2050, as per accounting firm Ernst and Young. Building new energy assets and infrastructure will require massive amounts of minerals and metals, particularly copper, lithium, nickel and iron ore. Resource nationalism and geopolitical tensions will, however, threaten to disrupt supply, push up costs and increase market volatility.

As developed countries and blocs like the EU resort to carbon border tax on imported goods, to safeguard domestic industries, the measures would contradict their commitment to support green transition in developing countries and raise the risk of trade conflicts.

This was first published in the 1-15 January, 2025 Print edition of Down To Earth