The 1980s and early 1990s were a time, the world over, of increasingly stereotypical confrontations between industry and environmentalists. Ecological considerations formed no part of industrial productive strategies, argued environmentalists. Industry treated the ecosystem as a vast self-replenishing raw material procurement facility, and as a convenient dumping site. Nonsense, thundered industry captains. They would not be blackmailed by bird-lovers; nothing could compromise profit-margins.

The 1980s and early 1990s were a time, the world over, of increasingly stereotypical confrontations between industry and environmentalists. Ecological considerations formed no part of industrial productive strategies, argued environmentalists. Industry treated the ecosystem as a vast self-replenishing raw material procurement facility, and as a convenient dumping site. Nonsense, thundered industry captains. They would not be blackmailed by bird-lovers; nothing could compromise profit-margins.

From the early 1990s began a time when this confrontation began to resolve itself. The factors that caused this turn of affairs were wide-ranging -- civil society's increasing experience of the effects of environmental abuse and refusal to countenance corporate denial; new management paradigms and practices that spoke of environmental efficiency as positive; shareholder pressures; and, most crucially, policy directions and regulatory measures by governments that forced industry to look for a clean-up act. In essence, there emerged a realisation that finite resource use had embedded economic benefits.

This confrontation has not ended. But in the West, it has led to strategies -- technological, managerial, process- and product-based -- where economic and environmental considerations are no longer thought to be incompatible. Companies in the West have realised that balance sheets and a cleaner environment do sometimes complement each other.

What about Indian industry? It is mired in poison, and must now look for a cure. By hook, crook or vision.

The simplest way out is the technological fix: import. But sadly, this won't work. Because solutions offered by the developed world apply only to the large-scale sector, while the major challenge in India lies in developing clean technologies or viable pollution control systems that work for the medium and small sectors. Both sectors rely heavily on natural resources, and are heavily entrenched in the rural economy. The small-scale agro-residue based paper and pulp industry, tanneries, or molasses-driven distilleries do not exist in the West. But in India, they are part of a small-scale sector that accounts for 40 per cent of industrial production, 35 per cent of direct exports and -- here is the rub -- 60 per cent of total industrial pollution. Each year, between 100,000 and 150,000 small-scale units open shop, leading to a question: will such entrepreunarial boom lead to ecological bust?

It need not. But where is the awareness that the search for an indigenous cure has to begin at home?

In its 10th five-year plan, the government of India envisages an 8 per cent GDP growth rate, for it wishes to double the country's per capita income in the coming decade. This, says the plan, requires a 10 per cent growth rate in the industrial sector. The plan is a noble one, except that this growth is not going to be a pollution-neutral one. It cannot be so. It cannot be so because government's regulatory mechanisms are either non-existent or completely weak. Industry today guzzles resources and pollutes freely because it can do so; what might happen in the future if such a scenario persists is too frightening to even imagine. On its part, industry's investment in research and development is as miniscule as the government's intent to achieve pollution-neutral growth: on an average, it is a pathetic 0.1 per cent of total turnover. In addition, most Indian industrialists prefer informal solutions to structural problems, solutions such as the readily-corruptible local politician or toxic sludge surreptitiously disgorged into a stream at night.

Perhaps the greatest problem is that environmental managers in Indian companies today are a marginalised lot. They could lead their companies to pollution-neutrality, but currently lack fiat, or clout. This became clear when the Green Rating Project of the Centre for Science and Environment set up an Environment Manager's Award to make visible the efforts made by professionals in imbuing companies with an ecological vision. Such managers exist only in large companies; they are not taken seriously. Environmental commitment, it seems, isn't serious business enough.

The environmental manager will have to be the chief innovator -- by finding solutions to the challenges of this century.

Currently, industry guzzles about 22 per cent of the total freshwater used worldwide. By 2025, this figure is expected to go up to 24 per cent, says the World Bank's World Water Development Report 2001.

Currently, industry guzzles about 22 per cent of the total freshwater used worldwide. By 2025, this figure is expected to go up to 24 per cent, says the World Bank's World Water Development Report 2001.

Industry's use of water acts as a double-edged sword: it puts immense pressure on local water resources, and it devastates the environment through wastewater discharge. Essentially used as input, mass and heat transfer media and for other miscellaneous purposes, a very small fraction of the water is actually consumed. About 90 per cent of the water used in major water-consuming industries is ultimately discharged as wastewater. According to the CPCB, in 2001, Indian industry consumed 40 km 3 of water and discharged 30.31 km 3 of wastewater. The issue of water use in industries, therefore, has to be addressed within these two interlinked paradigms.

Industry does not only use up a lot of water, it does so in an extremely inefficient manner. Compared to globally acceptable standards, the water consumption efficiency (water consumed to produce a unit product) of Indian industry is dismal (see table below: Guzzlers Inc). Thermal power plants (TPPs) are the major consumers, accounting for a staggering 88 per cent of the total water consumed by industry (see table below: Water use). In a scenario where the availability of water is dipping alarmingly, this is a recipe for disaster.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

To successfully confront the challenge of water, Indian industry will have to aim at zero freshwater demand and zero effluent discharge. So far, water management in Indian industry has revolved around two basic aspects: raw water treatment to meet end-use requirements and effluent treatment for meeting discharge standards. Isolated, but noteworthy, examples of innovation do exist: the Chennai Petroleum Company Limited, for instance, treats municipal sewage to meet its process water requirements and is on its way to close its water cycle as well.

|

||||||||||||||

Ineptly. One word that describes the way Indian industry produces and gobbles energy. And because it is inept, it gobbles more than what is necessary. The end result: more pollution.

Ineptly. One word that describes the way Indian industry produces and gobbles energy. And because it is inept, it gobbles more than what is necessary. The end result: more pollution.

In 1999-2000, 52 per cent of the total coal consumed in the country (76.20 million TOE) was used for power generation by thermal power plants (TPPs). The net power generated from this coal -- after accounting for conversion losses in generation (49.98 million TOE) and auxiliary generation in power plants (2.36 million TOE) -- was just 23.86 million TOE: meaning a power generation efficiency of 31.3 per cent. If we take into account transmission and distribution (T&D) losses of about 8 per cent of gross coal input, the total power generation efficiency from coal stood at a bare 23.3 per cent.

This unbelievably inefficient generation is at the core of all the energy challenges facing the nation. And it is powered by obsolete and wasteful combustion technology and poor quality of coal.

So what is the Indian government doing about it? In its Blueprint for Power Sector Development (2001), the MOP states that India will need an additional 100,000 megawatts (MW) of power by 2012. And this demand will be met not by improving technology to clean the coal and enhancing existing generation efficiency, but mainly by constructing additional power plants at an investment of Rs 800,000 crore.

The MOP's blueprint also promises the introduction in India of what it calls super critical technology, which has slightly higher efficiency than the existing TPPs. However, what it conveniently bypasses is that this version is just a modification of the existing technology, spews forth the same amounts of fly ash and is already considered obsolete in the West. With the gargantuan scale of the challenge it faces, India can do without half-baked solutions such as these. What it needs instead are clean coal combustion technologies such as fluidised bed combustion (FBC) and integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) that promise significantly higher efficiency and lower pollution. While FBC is a proven tech nology in India, IGCC is still in its infancy. However, IGCC offers a more efficient way of generating power: it uses high-pressure coal gases exiting a gasifier to power a gas turbine, and the exhaust from the gas turbine to run a conventional steam turbine. This 'combined cycle' turbine arrangement, not feasible in conventional combustion, gives IGCC an efficiency potential of 60 per cent compared to conventional combustion plants' 30 per cent. Investment in research and local adaptation of IGCC is, therefore, the imperative.

The FBC technology, which is currently available till IGCC becomes viable, has its advantages. Retrofitting existing TPPs with FBC can increase the energy efficiency level to 40-45 per cent. The economics of this transition also seems to be sound. According to the estimates of the Green Rating Project, India can upgrade its entire existing TPPs' capacity (about 74,700 MW) to FBC technology within the MOP's budgeted investment of Rs 800,000 crore, and still have Rs 575,900 crore left over for capacity addition and augmentation of T&D infrastructure .

The country's TPPs generation capacity, thus, can get a 45 per cent jump with an investment which is only 30 per cent of the projected Rs 800,000 crore (see box: A case for clean coal combustion technology) -- without any additional consumption of coal or construction of new power plants.

The MOP's policy on the size of its proposed plants is also a bloomer. It envisages setting up large TPPs (more than 600 MW capacity), which entail centralised generation and distribution spread across a vast area. Though large TPPs can lay claim to improved efficiency of scale, the poor status of T&D infrastructure and management in India will eliminate this advantage. Moreover, such a policy will put breakers in the way of a shift to decentralised, renewable energy technologies that seems to be the future.

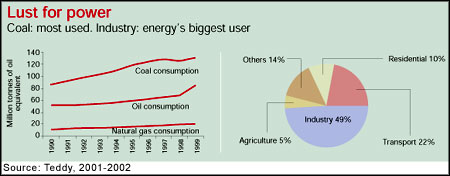

Industry, the largest consumer of energy in the country, accounts for about 49 per cent of the total commercial use; coal and lignite meet about three-fourth of this demand. As with generation, inefficiency marks the consumption of energy in India.

Within industry, the iron and steel sector leads in consumption with around 10 per cent of the total. Energy costs represent about 30-35 per cent of the total production cost in the sector. Despite this, the average energy consumed for making one tonne of crude steel in India is in the range of 30-40 GJ -- very high compared to global standards (18-20 GJ) (see table below: Abuse of power).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

With depleting global carbon-based fuel reserves and ever-burgeoning oil bills, India needs to reach for viable options, such as technologies that use renewable natural resources like biomass, water, wind and solar energy. The development and promotion of these technologies -- an immense potental for which exists in the country -- was started more than a decade ago. But even today, their contribution has reached just 3,000 MW-- less than 3 per cent of the total grid capacity. (see table below: Untapped)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The case of India's agro-based pulp and paper mills is representative of most small and medium enterprises (SMEs) operating in the country: low on resources, low on motivation to turn clean, and therefore, low on efficient, non-polluting technology.

The case of India's agro-based pulp and paper mills is representative of most small and medium enterprises (SMEs) operating in the country: low on resources, low on motivation to turn clean, and therefore, low on efficient, non-polluting technology. India's 2,500 tanneries churn out 1.8 billion square feet of leather every year. They earn the country US $6 billion annually as foreign exchange. They also discharge about 24 million cubic metres of wastewater with high COD, BOD and TDS concentrations, and about 0.4 million tonnes of hazardous solid wastes per annum (Environmental Management in Selected Industrial Sectors, CPCB and MEF, 2003).

India's 2,500 tanneries churn out 1.8 billion square feet of leather every year. They earn the country US $6 billion annually as foreign exchange. They also discharge about 24 million cubic metres of wastewater with high COD, BOD and TDS concentrations, and about 0.4 million tonnes of hazardous solid wastes per annum (Environmental Management in Selected Industrial Sectors, CPCB and MEF, 2003). Modern agriculture: the boon and the bane of India's teeming millions. The boon, because it has ensured that the nation's crop fields remain fecund. The bane, because it has bred a poison that is seeping into our veins through the food we eat and the water we drink. Every day. Every moment.

Modern agriculture: the boon and the bane of India's teeming millions. The boon, because it has ensured that the nation's crop fields remain fecund. The bane, because it has bred a poison that is seeping into our veins through the food we eat and the water we drink. Every day. Every moment.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The diverse profiles of the nominees pointed to the variety that existed in the profession. Vice presidents and general managers, directors and senior managers vied for the top spot. Working experiences ranged from more than 30 years to less than two years; responsibilities, from providing overall guidance and vision to the environmental aspect of the business to mere liaison with state pollution control boards. The survey also generated information on critical trends in the state of environment management in Indian industry, and on the kinds of environment protection initiatives taken.

To begin with, all the 74 nominees came from large-scale companies (the second group in Indian industry). Nominations from small and medium enterprises were conspicuous by their absence.

Majority of the nominees represented well-known companies that had a presence in global markets. Fourteen nominees were from MNCs. This indicates that liberalisation of the Indian economy, its increasing interaction with global markets, and corporate image are contributing to pushing companies towards better environmental management.

Of the 74 nominees, only 19 represented a department that catered exclusively to environment. The rest came from departments which environment shared with other specialities like quality control, health and safety, operations, production or R&D. Though the association of environment with health and safety is now being recognised as valid, the others are symptomatic of the lip service that companies usually pay to environment management.

CSE also found that a majority of the nominees did not have enough decision-making powers. More than 60 per cent of them represented middle management (managers, deputy general managers, etc); only nine managers belonged to the higher management level (vice presidents, directors, etc).