.jpg?w=320&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)

.jpg) Sometime in June 2009, the West Bengal chief minister’s office forwarded a complaint to the state pollution control board (SPCB) about three sponge iron factories in West Medinipur district.

Sometime in June 2009, the West Bengal chief minister’s office forwarded a complaint to the state pollution control board (SPCB) about three sponge iron factories in West Medinipur district.

A team was dispatched to Jhargram subdivision. It found a thick layer of grey dust coating trees and pathways, and noted that the factories stored iron ore and waste in the open; these are carried away by the wind. A month later, the state’s Pollution Control Appellate Authority indicted the three units for causing “colossal damage” to the environment and ordered immediate closure of one factory that was a repeat offender; the other two were asked to comply with pollution norms and guidelines. But the repeat offender— Rashmi Cement sponge iron plant—did not shut. Reason: the SPCB suspended the closure order, citing the appellate authority order that allowed the factory to operate once faults are rectified.

|

||||||||||

.jpg) Pollution from these coal-based factories is more acute in Chhattisgarh. The state has close to 70 sponge iron factories, clustered mainly in Siltara and Urla in Raipur district and in Raigarh district. An estimated 60 more are operating illegally. The region is also the hub of public protests. In June 2009, about 300 people took to the streets to protest the health effects of pollution from the factories of Siltara and Urla. They complained of respiratory disorders and skin allergies. The authorities issued notices to 45 factories for not installing or using pollution control equipment.

Pollution from these coal-based factories is more acute in Chhattisgarh. The state has close to 70 sponge iron factories, clustered mainly in Siltara and Urla in Raipur district and in Raigarh district. An estimated 60 more are operating illegally. The region is also the hub of public protests. In June 2009, about 300 people took to the streets to protest the health effects of pollution from the factories of Siltara and Urla. They complained of respiratory disorders and skin allergies. The authorities issued notices to 45 factories for not installing or using pollution control equipment..jpg) In Andhra Pradesh’s Mehboobnagar district, people moved court when protests and pleas to the government did not work. Initially no action was taken on the petition but later factories in the area were directed to jointly deposit Rs 3 crore with the district authorities as token compensation for farmers. The amount was decided on the basis of Kharif crop lost.

In Andhra Pradesh’s Mehboobnagar district, people moved court when protests and pleas to the government did not work. Initially no action was taken on the petition but later factories in the area were directed to jointly deposit Rs 3 crore with the district authorities as token compensation for farmers. The amount was decided on the basis of Kharif crop lost..jpg) A blanket of smog envelopes Kuarmunda and Bonai subdivisions of Odisha’s Sundargarh district every morning. Area residents attribute it to emissions from sponge iron factories nearby that switch off their emission control devices—electrostatic precipitators (ESPs)—at night. The reason these factories get away with such offences is weak rules and weaker enforcement.

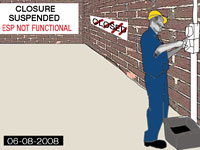

A blanket of smog envelopes Kuarmunda and Bonai subdivisions of Odisha’s Sundargarh district every morning. Area residents attribute it to emissions from sponge iron factories nearby that switch off their emission control devices—electrostatic precipitators (ESPs)—at night. The reason these factories get away with such offences is weak rules and weaker enforcement.

|

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

| Govinda Impex in West Bengal has been repeatedly served notices for violations | |

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Notices issued were suspended time and again but the factory still did not rectify faults | |

| Illustrations: Vaibhav Raghunandan |

.jpg) showed ambient air SPM of 2,025 μg/m3 which is about 20 times the present standard. No action was taken against the two, and the list of such factories is unending.

showed ambient air SPM of 2,025 μg/m3 which is about 20 times the present standard. No action was taken against the two, and the list of such factories is unending.

|

—Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and West Bengal. A total of 449 inspection reports, including night inspection reports, were made available for the period 2006-2009. They contained status of pollution control measures, compliance with norms and notices served. In addition to these, 265 stack monitoring reports were made available for the period 2006-2010 for Odisha, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal. Hundred and eighty nine ambient air quality reports were also provided for factories in Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

—Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and West Bengal. A total of 449 inspection reports, including night inspection reports, were made available for the period 2006-2009. They contained status of pollution control measures, compliance with norms and notices served. In addition to these, 265 stack monitoring reports were made available for the period 2006-2010 for Odisha, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal. Hundred and eighty nine ambient air quality reports were also provided for factories in Odisha and Chhattisgarh..jpg) The factories have a worse record when it comes to operating ESPs. Data shows, 37 per cent of the factories had non-functional or partially functional ESPs. Even where ESPs were in running condition, leakage of emissions from kilns were recorded in 60 per cent inspection reports. Odisha reports showed leakage in 37 per cent kilns with ESPs. In West Bengal, 92 per cent factories recorded emissions despite ESPs.

The factories have a worse record when it comes to operating ESPs. Data shows, 37 per cent of the factories had non-functional or partially functional ESPs. Even where ESPs were in running condition, leakage of emissions from kilns were recorded in 60 per cent inspection reports. Odisha reports showed leakage in 37 per cent kilns with ESPs. In West Bengal, 92 per cent factories recorded emissions despite ESPs.

|

.jpg) If one were to compare steel consumption figures, Indians lag far behind the rest of the world. Against the world average of 215 kg, per person steel consumption in India is just 50 kg a year. This consumption gap is likely to reduce in coming years. With rapid economic growth, steel requirement for housing, infrastructure and industry is poised to grow significantly.

If one were to compare steel consumption figures, Indians lag far behind the rest of the world. Against the world average of 215 kg, per person steel consumption in India is just 50 kg a year. This consumption gap is likely to reduce in coming years. With rapid economic growth, steel requirement for housing, infrastructure and industry is poised to grow significantly.

Post liberalisation, steel production in India has grown seven to eight per cent annually. At this rate, which many experts consider sustainable, steel production will jump to 300 million tonnes (MT) in 2030 from 60 MT at present.

Traditionally, steel was manufactured from pig iron using blast furnace. India does not have reserves of coking coal, an important raw material for blast furnace route to make steel, and presently imports about 70 per cent of its coking coal requirement. This pushes up steel prices. Therefore, blast furnace route cannot meet the 300 MT target.

The other way to produce steel is through recycling used steel—the steel scrap route. Currently, about 15 per cent of steel production in India is from scrap. Due to limited scrap availability and ever increasing prices of imported scrap, not more than 10 per cent of steel can be produced from scrap by 2030.

The only option left is production of steel through DRI (sponge iron) route. DRI can be produced using gas but it is expensive and gas availability is not assured. So, the real option is to produce steel using non-coking coal, through DRI. In 2030, more than 60 per cent of the steel produced in India will come from coal-based sponge iron. This means more than 200 MT of sponge iron and hundreds of sponge iron factories. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop an action plan for the sector to contain its environmental impact.

Strengthen enforcement

It is evident that our current system of environmental monitoring and enforcement is not working. The problem with SPCBs is lack of capacity and accountability, non-transparent functioning and corruption. This has happened largely because of neglect and politicization of these institutions. The result is these institutions are incapable of taking strong enforcement actions. Industries pollute as there is no credible deterrence for non-compliance. The charade of issuing show cause and closure notices and imposing small bank guarantee is not going to solve the problem.

What we need is a system that ensures non-compliance is dealt with strictly. Increasing capacity, transparency and accountability of SPCBs is the first step in this direction. We then need to amend the Environment Protection Act to increase penalty amounts and set up a civil-administrative mechanism that can impose penalties without taking recourse to the lengthy legal process.

Bigger factories better

But this will not work unless we tighten technology and emission benchmarks for the sector. ‘Bigger the better’ is the mantra for the sector. Kilns with less than 200 TPD capacity cannot adopt cleaner technologies like an AFBC boiler that burns kiln gas to generate energy. Similarly, a boiler to burn char is not economically viable for smaller factories. These two technologies alone can reduce emissions significantly. It is for this reason that the government must devise a plan to phase out smaller kilns and immediately stop commissioning of kilns with less than 200 TPD capacity.

Material handling is a major source of fugitive dust and needs to be tackled by implementing mandatory technology and management norms. Ultimately, there has to be further technology development in this sector as the current technology, even with all refinements, is still polluting. We need a technology mission for the sponge iron sector.

With inputs from Jyotika Sood