It is a universe of its own—an expanding universe that has its own producers and consumers, its entrepreneurs, its markets, its passionate aficionados of scientists and evangelists. It is a universe that is governed by a different set of regulations and plays strictly by the rules, for the most part. In the politics of agriculture, its ideology is controversial since it goes against mainstream wisdom, almost heretical since it sets out to disprove the dominant chemical-driven theology of the past 60 years. We are talking about organic farming.

It is a universe of its own—an expanding universe that has its own producers and consumers, its entrepreneurs, its markets, its passionate aficionados of scientists and evangelists. It is a universe that is governed by a different set of regulations and plays strictly by the rules, for the most part. In the politics of agriculture, its ideology is controversial since it goes against mainstream wisdom, almost heretical since it sets out to disprove the dominant chemical-driven theology of the past 60 years. We are talking about organic farming.

Why is organic farming controversial? At a fundamental level, it sets out to prove that you do not need chemical pesticides and synthetic fertilisers to produce adequate quantities of food. Organic farming works in harmony with nature by using simple techniques and material: recycled and composted crop waste and animal manure; crop rotation; legumes to fix soil nitrogen; encouraging useful predators that eat pests and natural pesticides; and a careful husbanding of water resources. The bottom line: increasing genetic diversity and conservation. It also means that no genetically modified crop is part of this ecosystem. The result: healthier farmers and risk-free food.

It is a philosophy that has caught the fancy of some unlikely players. Some have given up well-heeled jobs in the Silicon Valley, others a lucrative legal career. There are doctors who have turned into farmers, and management professionals into organic retailers. In all cases, there was a desire “to return to natural methods of cultivation sans chemicals” and to grow “real food that tastes like it used to”.

|

|

|

“Our concept is different,” explains Somesha B, CEO of Sahaja. “We are working with farmers, helping them to convert to organic and provide marketing assurance. So we keep our margins low: 10-15 per cent mark-up for wholesale and 20-25 per cent for retail. In any case, the profits go back to the farmer since they have shares in the company.” Turnover last year was Rs 52 lakh, but Sahaja is certain revenue will double this year.

One of the biggest grassroots success stories is of Morarka Foundation which, with its 100-plus project locations covering 19 states, has brought around 100,000 farmers under the umbrella of Morarka Organic. This has helped it understand the different agro-climatic problems and gain expertise in handling over 130 crops/products which, it says, form its core portfolio and are offered both as farm grade as well as processed and in retail packs that are sold under the Down to Earth brand (no connection with this magazine).

There are others like the feisty H R Jayaram who gave up a prosperous law practice to become an organic farmer-cum-retailer. He has set up what is probably India’s first organic hotel, The Green Path, in a Bengaluru suburb. Jayaram’s aim is to fire others with his passion and “to create replicable models that will inspire more people to take up organic”. Sahaja and enthusiasts like Jayaram have held regular organic food melas, which has helped make Bengaluru India’s undisputed organics capital. Restaurants, coffee shops and stores like Simply Organics run by another farming buff Govind Kabadi make for zesty organic profile for this city. Aiding this is the state government which gives Karnataka farmers a big helping hand in finding outlets for their produce.

But the corner organic store with crowded shelves is not the dominant image of organic retailing. The familiar milieu is the chic store in tony localities that sell beautifully packaged products that come with all kinds of certification—from NPOP (National Programme on Organic Production), which is the Indian standard, to those of the EU and the US. Here premiums are high since products come through many layers of marketing. The other place where one is bound to find such products are supermarket chains like Chennai-based Spencer’s which has a national footprint. Says a spokesperson for the chain: “We are a food-first multi-format retailer and sell a wide range of brands like 24 Letter Mantra, Down To Earth, Pro Nature and Pro Organic.” Growth has been phenomenal. Starting with two brands in 2006, Spencer’s organic category has grown by 300 per cent in last three years. Besides, its offerings which were restricted to commodities like cereals, pulses and spices, are spilling into a wide assortment from breakfast cereals to snacks and soups. For those who have the money, such outlets are a cornucopia of natural goodness.

Delhi-based Fabindia, which caters to the well-heeled and trendy customer, is a leading purveyor of organic foods, its elite stores across the country stocking carefully selected products. Ashima Agarwal, who heads the organic foods division, is unwilling to disclose the amount of business this segment brings in, but says: “Though small, organic foods are witnessing growth in terms of customer base and consumption. We started with 70 products and today offer more than 300 products and are still growing.” For William Bissell, Fabindia founder, the foray into organics from clothes, furnishings and traditional crafts was inspired by a book Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappe, a 1971 bestseller which advocated ecologically sound production of food. “Then when I was in the US, I worked on the organic farm of Gordon Ridgeway who was a purist and influenced me greatly,” says Bissell. Although he would like to keep fresh produce in his stores, there are too many logistical issues.

Logistics are critical to the success of organic farming and the reason such produce is far too expensive for the ordinary consumer. For instance, products sold by non-profit Navdanya are more expensive than similar items that are not organic. Founder Vandana Shiva has an explanation: “For me, organic farming is about livelihood and about sustainability and justice. When a farmer practices organic agriculture, he knows how to sustain his farm with natural resources; he is able to feed himself and his family; takes care of earth by giving natural resources back in forms of bio-fertilisers and bio-pesticides without polluting the environment.” Naturally, all this comes at a price since the government offers no help at all.

The booming growth in organic foods may well spell hope for the small farmer. With health-conscious and cash-rich customers ready to pay the premium for organic food, the market is expanding in dramatic ways. High-end, imported organic has also come to India. The first such is businessman Dilip Doshi’s Organic Hauswhich which has opened in Ahmedabad and Mumbai. For Doshi it is business pure and simple; he does not claim to promote organic because it is better for the environment or for the farmer. Every product in his uber-luxury stores is imported from Germany and Austria.

“Mine is a concept store. It tells the story of the evolution of globally benchmarked products. You can close your eyes and say this is organic. I could not find any genuine organic foods in India,” declares Doshi. That could come as a crushing blow to all the organisations, farmers and activists who have struggled to put Indian organic on the global map. But fortunately in Europe and the US, which together account for 96 per cent of the market, India’s credentials are respected even if it accounted for just a fraction of the US $59 billion global market for certified organic food and drink. India’s exports in 2010-11 totalled just Rs 550 crore, according to Manoj Kumar Menon, executive director of the International Competence Centre for Organic Agriculture or ICCOA, which is a knowledge centre for all facets of organic agriculture and also helps provide market linkages to all those engaged in organic agriculture.

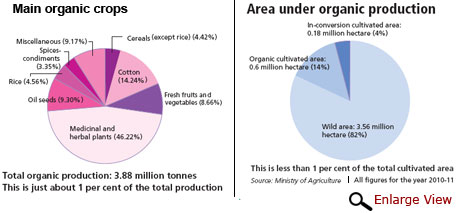

ICCOA is a crucial link to the market with its international trade fair Bio Fach India which draws over 100 global companies and thousands of visitors to its annual event. Menon is confident that India will become a significant player in the next four years when production is expected to touch Rs 4,000 crore, a huge leap from the current Rs 675 crore. By then, the global trade is expected to cross US $104 billion in 2015 at an estimated annual rate of 12.8 per cent. On the global organic map, India is a speck; it does not figure in the list of the top 10 countries. According to data released in June 2012 by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) and the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture of Switzerland, there was a total of 37 million ha of agricultural land that was organic in 2010. In addition, the organic universe had another 43 million ha of non-agricultural areas, up from 41 million ha in 2009.

What was India’s share? It had 0.6 million ha under cultivation, another 0.18 million ha under conversion along with wild area of 3.56 million ha. IFOAM statistics also put the total number of organic farmers worldwide at about 1.6 million, with the largest number, a whopping one million of them, in India. This is where our organic story gets truly interesting. In fact, the slight dip in organic agriculture area in 2010 was on account of India which reported the loss of 0.4 million ha of organic cultivation. But that trend is reversing. Says A K Yadav, director of National Centre of Organic Farming (NCOF): “The declining trend has been reversed and the area under certification process during 2011-12 is likely to be more than one million hectares.” He also makes the point that all the statistics with NCOF are for the area which is registered under certification process. “There is no reliable data on farmers doing organic but have not opted for certification.”

In all probability it means that organic cultivation is more widespread than estimated, although the Ministry of Agriculture is doing its best to undermine this through its various programmes. For instance, it has allowed its flagship scheme Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana to be used by states to convert tribal areas or the organic wild centre to conventional farming through the provision of free hybrid seeds in kits that also contain chemical pesticides and fertilisers. There is also the looming threat of climate change and its impact on agriculture.

While Krishi Bhavan has finally asked Ardhendu Sen, a former bureaucrat now with TERI, to draft a policy document for the promotion of organic agriculture, farmers are deciding on their own what’s in their best interest.

Innovative farm-to-home trail

WHEN 29-year-old Sunil Gupta (left) gave up his job as operations manager with a European GIS systems manufacturer in 2001 to try his hand at organic farming, it seemed a romantic idea. He would grow safe, wholesome crops without chemical pesticides and fertilisers on his 14-ha farm in Sirsa, Haryana. It turned out to be a nightmare. “The first year I failed miserably. I sought help from the Haryana Agriculture Department. But they had no clue what I was trying to do.” WHEN 29-year-old Sunil Gupta (left) gave up his job as operations manager with a European GIS systems manufacturer in 2001 to try his hand at organic farming, it seemed a romantic idea. He would grow safe, wholesome crops without chemical pesticides and fertilisers on his 14-ha farm in Sirsa, Haryana. It turned out to be a nightmare. “The first year I failed miserably. I sought help from the Haryana Agriculture Department. But they had no clue what I was trying to do.”Gupta travelled across Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan to know how agriculture was practised before the Green Revolution, which advocated generous lashings of synthetic fertilisers and chemical pesticides. Gupta began farming using manure and compost and biodynamics—sowing and planting as per astronomical calendar. The yield dropped, but the soil started regenerating and the food was safer to eat. Gupta then got neighbouring farmers to turn organic cultivators. For the manure, he hit upon an innovative idea. Gaushalas, run by local communities as a relgious duty, had no money to feed the cows and found disposal of dung a problem. He persuaded the farmers to accept feed for the cows in return for the dung. Now, there is enough manure for the 1,214 ha belonging to the 1,500 small farmers who are members of Dharani Suphalam, a primary producers’ society. Dharani Suphalam produces about two tonnes of fruits and vegetables daily. How does this reach consumers? Gupta, as president of the society, ties up with top organic stores in Gurgaon, Jalandhar and Ludhiana. Dharani Suphalam has a marketable surplus of 1,000 tonnes of wheat, 500 tonnes of rice and 100 tonnes of mustard oil. Talks are under way with exporters but are yet to translate into contracts.  But prospects are improving with players like Ashmeet Kapoor (right) who left an electrical engineering job in the US. Kapoor, 26, is the last vital link in getting fresh veggies into homes. He has set up I Say Organic, a home delivery service that works in south Delhi and Gurgaon. Its one cold store and four vans handle about two tonnes of produce daily from Dharani and producers in Himachal Pradesh. The vans ferry veggies on orders placed on the company’s website or by phone. Prices are high but then, Kapoor says, he is giving farmers 25 per cent premium over mandi prices. But prospects are improving with players like Ashmeet Kapoor (right) who left an electrical engineering job in the US. Kapoor, 26, is the last vital link in getting fresh veggies into homes. He has set up I Say Organic, a home delivery service that works in south Delhi and Gurgaon. Its one cold store and four vans handle about two tonnes of produce daily from Dharani and producers in Himachal Pradesh. The vans ferry veggies on orders placed on the company’s website or by phone. Prices are high but then, Kapoor says, he is giving farmers 25 per cent premium over mandi prices. |

The Centre has no policy on organic farming but 10 states are promoting it

Manoj Kumar Menon of the International Competence Centre for Organic Agriculture (ICCOA), a knowledge centre on organic agriculture, has an interesting story to relate on how the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) views organic farming.

Manoj Kumar Menon of the International Competence Centre for Organic Agriculture (ICCOA), a knowledge centre on organic agriculture, has an interesting story to relate on how the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) views organic farming.

Some years ago, ICCOA proposed a research study to prove the scientific validity of organic agriculture since mainstream scientists were dismissive of this system of growing crops without synthetic fertilisers and chemicals. “Organic agriculture in a holistic sense is sustainable agriculture but ICAR is not ready to accept it,” says Menon.

The project proposal that was put to ICAR’s National Agricultural Innovation Project (NAIP) was to test organic systems in different agro- climatic zones and with different crops (cereals, pulses, spices etc). The outlay was initially Rs 42 crore but it was whittled down to Rs 12 crore. The proposal cleared four committees, including technical, and finally in February 2008 reached the then director general of ICAR Mangala Rai.

“A distinguished scientist Tej Pratap Singh (vice-chancellor, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology) had just started making the presentation. But after just the third slide Rai observed, ‘I do not see any science in organic agriculture’.” That, in fact, sums up the general attitude of mainstream agriculture scientists whose thinking has been shaped by the late Norman Borlaug, father of the Green Revolution, who was a firm believer in the use of synthetic fertilisers to push up crop yields. Borlaug had termed as “ridiculous” the idea that organic farming was better for the environment because it gave lower yields and therefore required more land to produce the same amount of food.

Supporters of organic point out that on the contrary the shift from expensive high-input agriculture to knowledge-intensive practices is much kinder to the environment with the emphasis on using naturally available resources (green manure and cowdung), biopesticides, crop rotation and water conservation. But almost everything that the Ministry of Agriculture and ICAR’s vast network of public research institutions does undermines sustainable farming.

Official policies are stuck in what India’s leading authority on biomass, Om P Rupela, terms, “the NPK mindset of mainstream scientists”. NPK stands for chemical elements nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium that are commonly used in fertilisers. “They calculate that the same amount of synthetic NPK that is used in conventional agriculture has to be replaced by an equivalent amount of biomass nitrogen and then claim that India doesn’t have those quantities.”

|

A K Yadav, director of National Centre of Organic Farming, the Ministry of Agriculture’s nodal agency, says it is difficult to say which of these states has the best organic policy but he zeroes in on Uttarakhand and Sikkim as the best. “As far as taking the movement to the people is concerned, Sikkim is more successful. But if we are looking at market facilitation, networking of farmers and ensuring that farmers get a premium, Uttarakhand is ahead.”

A K Yadav, director of National Centre of Organic Farming, the Ministry of Agriculture’s nodal agency, says it is difficult to say which of these states has the best organic policy but he zeroes in on Uttarakhand and Sikkim as the best. “As far as taking the movement to the people is concerned, Sikkim is more successful. But if we are looking at market facilitation, networking of farmers and ensuring that farmers get a premium, Uttarakhand is ahead.”

|

Karnataka, the first state to announce an organic farming policy in 2004, is carrying forward research to strengthen organic farming. Biocentre, a certified 17-ha spread of plantations and nurseries, is developing workable models of organic production systems with medicinal and aromatic plants as one of the components. K Ramakrishnappa, additional director in the horticulture department, who looks after organic agriculture, says that one of the more practical initiatives the state has taken is to set up the Jaivik Krishik Society that clubs 47 farmers’ groups and is the nodal agency to facilitate group certification and marketing. It has also set up a Jaivik Mall that offers ample space for farmers wanting to sell their produce directly to consumers.

Another remarkable experiment that Down To Earth would like to highlight is the non-pesticide management (NPM) initiative of Andhra Pradesh. This has freed an impressive 1.5 million ha and 1.5 million farmers from the tyranny of chemicals through a community managed sustainable agriculture (CMSA) initiative. Interestingly, the initiative was launched by the Andhra Pradesh Ministry of Rural Development and not by the Agriculture Department. The fundamental objective of CMSA is to provide healthy food, healthy crops, healthy soil and a healthy life to farmers by ensuring food security locally.

The CMSA philosophy does not necessarily endorse organic as the ultimate objective although both work towards the similar objective of eliminating chemical inputs. Explains D V Raidu, director, CMSA, “Our mandate is to raise the incomes of small farmers, eliminate poverty and liberate ourselves by unlearning the practices of the past. Organic agriculture, on the other hand, leads to tunnel vision since its driving force is only the premium.”

Raidu’s contention is that organic market dynamics are not in the farmer’s hands—true enough, since there are widespread complaints that retailers and NGOs are ripping off the growers—and, therefore, the focus should be on “sustainable, viable and remunerative agriculture”. He also asks why “if organic is so good, it so minuscule? Besides, the premium is earned only on scarcity of supplies.”

However, CMSA, he hastens to add, is ready to help farmers with certification if they want it. “The choice is the farmer’s. The best part of CMSA is it is a programme that fits all needs.” In fact, the groundwork is done to assist farmers with the Participatory Guarantee System certification, a cost-free way of providing quality assurance. But Raidu takes pride in the following statistics: 124 villages declared pesticides-free, 26 villages deemed organic. Not a bad record at all, although the programme only seeks to cut synthetic fertiliser by half, not bar it.

For the Union government, CMSA offers a silver lining: it is saving Rs 1.2 crore on fertiliser subsidy, while farmers are spared an expense of Rs 1.47 crore by eliminating pesticides and cutting fertiliser use.

Go to a meeting of organic farmers discussing the problems they face and usually there will be unanimity on one issue: they all hate APEDA. The reason: APEDA is the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, under the Ministry of Commerce, which set the norms for certification to help organic products find market abroad. Those norms were based on the European Union standards, said to be the toughest in the world.

The third party certification (TPC) is necessary for global trade in organics and India has 22 certifying agencies accredited by APEDA. But this kind of certification comes at a huge cost and requires a huge amount of documentation. It poses a serious challenge for India’s organic farmers, most of whom are small landholders with just about an acre (0.4 hectare) per family and are, for the most part, illiterate. How do they cope with the requirements of certification which are mandatory for earning the organic premium? The more serious impact is that it would stop the organic movement in its tracks.

Fortunately, alternative methods to guarantee the organic integrity of products have been developed for small domestic producers, known as the participatory guarantee system or PGS. The main characteristics of PGS are: low cost, involves minimal paperwork and makes farmers responsible for the success and integrity of their group. There are no intermediaries since the group will be supreme, with members responsible for conducting inspections of each other’s processes and guaranteeing the integrity of the product.

The PGS symbol is a familiar sight on a wide range of products from the Caffea from Keystone Foundation, Nilgiris, to peanut oil from Dharani of Timbaktu Collective of Anantpur district in Andhra Pradesh, spices of Organic Farming Association of India (OFAI) in Kerala and gur from OFAI in Maharashtra or Uttar Pradesh as well as fruit products from Grassroots Foundation in Ranikhet, Uttarakhand. Soon it will be seen on chillies from Uttarakhand. But while PGS works well in the domestic market, what happens to those who want to tap the export market?

According to NGOs and activists who work with marginal farmers, the fundamental flaw is that organic trade is governed by the commerce ministry. “The biggest drawback is that organic trade is the turf of the Ministry of Commerce and not the Ministry of Agriculture. As a result, it has become more market driven,” says Vandana Shiva of Navdanya. For her, “Organic is essentially a relationship between farmer and earth where they know and take care of each other.”

That may be so, but companies and export houses appear to have no problem with TPC which they say is inevitable for global trade. Says Rajashekar Reddy Seelam, managing director of Sresta Natural Bioproducts, a leading exporter: “The most important aspect here is the trust of the consumer, which has great potential to transform the market and more so the lives of farmers. We should not dilute the standards but make the process simpler.”

At the other extreme is the view that the differential norms for exports should be scrapped. Reflective of this attitude are the views expressed by Miguel Braganza, formerly with the OFAI which helped formulate PGS-India norms. He says: “TPC agencies operating in India are paid for at the poor farmer’s cost in the belief that export is the best policy. In actual practice, people in Europe eat healthy food grown in India and other Third World countries and collect the certification fees or ‘royalty’ thereon from the franchisee, while we eat food poisoned by pesticides from European manufacturers and pay royalty on the poisons, too!”

Gokul Patnaik, former head of APRDA who was instrumental in setting the norms, admits that the standards set by the body do discourage organic farming by small farmers. “But these regulations were not meant for the domestic market when they were formulated. Now is a good time to look at what we want from certification, which is an endorsement of trust.”

But for many farmer groups PGS itself is not working. Sunil Gupta, president of Dharani Suphalam, a primary producer society representing 1,500 organic farmers, says he would like to switch to PGS but complains that PGS is becoming excessively bureaucratic and is taking far too long to respond to applications. PGS is governed by National Centre of Organic Farming (NCOF) which comes under the Ministry of Agriculture and Dharani Suphalam’s application has been lying with it for the past eight months.

The group’s production is now certified by two TPC agencies and Gupta says the process is harrowing. “We have to maintain 345 records per farmer per season and it is a huge burden on our smallholders.” Together, the two agencies charge about Rs 2.5-3 lakh per year apart from another Rs 1 lakh each for inspections and sample testing. “If issues of certification are not resolved, it will be difficult for farmers’ groups such as ours to remain viable.”

A spokesperson for TPC, however, puts the ball back in the farmer’s court, saying: “Farmers should do their economics properly. The cost of certification should not exceed 0.5-1 per cent of their turnover. Every service, after all, comes at a cost.” According to him, farmers do not have to go for certification just because they are in organic farming; what they need is a good business plan. His defence is that certification agencies do not make big money because of various limitations and because “ultimately it is a volumes game”.

NCOF director A K Yadav says PGS in India is still in its nascent stage. “We are working on modalities of it and we need to create awareness about it.” He concedes that the certification normally takes two years and because “farmers are unaware about the intricacies when it comes to organic, this period extends to three years.”

But even if the certification is resolved, there are more problems ahead. Shiva says the Foods Safety and Standards Authority of India rules are also a hindrance to the growth of organic farming. “There are stringent rules for organic food products that will burden producers. Organic pulses, wheat and just about everything will require AGMARK, whereas normal produce will not need any certification or quality marks. “It is odd that organic producers have to prove their innocence, while those who sell food laced with chemicals and fertilisers are enjoying a free run in the market.”

There certainly is something about organic farming. It gets some people all charged up. So captivated are they by the idea of growing food in a safe and ecologically sound way that they abandon lucrative professions and well-paying jobs abroad to wallow in the good earth and stuff like cow dung, mulch and vermicompost. Nothing, it appears, is so satisfying as returning to farming, the natural way. Lawyers and doctors with a roaring practice, information technology professionals working in the US, coal merchants with a tidy business, management experts employed by multinationals—these are some of the organic buffs we came across as we researched this cover story.

Start with Manjunath Pankkaparambil, an ex-IT professional who runs Lumiere, the landmark organic restaurant in Bengaluru’s Martahalli suburb. A former consultant with Oracle and SAP in the US, Manjunath became acquainted with Ambrose Kooliyath, whom he describes a Gandhian activist and a farmer since 1997, during a visit home (Kerala). They decided to take up organic farming together and bought about four hectares (ha) in Munnar to grow English vegetables. That was in 2003. Then in 2009, the partners opened Lumiere in Kochi and a year later in Bengaluru.

The Kochi restaurant was closed earlier this year because there were not enough footfalls and sourcing was a problem. But the large (8,000 sq feet) Bengaluru restaurant-cum-store with 120 covers is open for business, and doing fairly well, says Manjunath. Clearly, the problems of running a fully organic restaurant—95 per cent of the ingredients are certified—are immense. Logistics of getting in fresh supplies meant that the Munnar farm did not work too well. Besides, it was difficult to get genuinely organic, free-range chicken (not injected with antibiotics and growth hormones) and eggs. So a 0.8 ha farm was bought in Bengaluru itself, one half for rearing chicken and the other for leafy greens. Other items are sourced from nearby farms—one of them run by a doctor in Udhagamandalam. The organic crowd is pretty good at networking and form close alliances both for business and pleasure.

Lumiere tries to get as close to fine dining as possible, although it is primarily a Kerala seafood menu. Is the restaurant bringing in profits. Not yet, although Rs 2 crore was invested in setting it up and regular cash infusions to keep it running. That does not seem to bother Manjunath, 46. “I sat 16 years in an office as a software professional. Now I am doing something that invigorates me, and it is environmentally sustainable.”

That is the usual story with such entrepreneurs, most of whom came into the organic field seven to eight years ago. Hardly any of them are making profits and yet far from being discouraged they intend to keep at it. The intrinsic value of what they are doing is enough recompense for them, they maintain. H R Jayaram, 53, also of Bengaluru, is in a different category because the money he made from his earlier legal profession allows him ample scope for trying out interesting new projects. A lawyer who returned to his roots by taking up farming, Jayaram, founder of Green Path Eco Foundation, started two organics stores, initially called Era Organics, to offload the fresh produce from his farm. That led to sourcing of other items from different sources to give customers a full range of household supplies. The difference is that in Jayaram’s store—one was shut down—customers will chance upon food not found elsewhere: candied papaya, millet sweets and other delicacies prepared at his farm. “I love what one can do with food, naturally grown food, and I like sharing it,” he says with his characteristic wide smile.

A year after the first store opened, Jayaram set up what appears to be the country’s first organic hotel. What makes a hotel organic? “Everything in Green Path is chosen with care. All amenities are green, the food is locally grown organic, the herbs are plucked from the hotel garden and the fabric we use are mostly organic and made with natural dyes. Even our soap and shampoo are organic,” he says with pride. The hotel, in a residential area of Bengaluru, has a soothing green ambience while its special menus are a treat for vegetarian food lovers.

Jayaram’s idea is “to create products and business models that will inspire others to follow the green path”—some of his friends have followed him in running organic farms—and to create strong links between consumers and their food. Organic farming, he firmly believes, changes one’s way of thinking, changes one’s life. “You learn to respect your soil, your water, your seeds. You take a holistic view of nature and life.”

|

|