The Aravallis, India’s oldest hills, don’t get in the way of progress. They pay for it

Some people see the slow decline of the Aravalli Range as an environmental disaster. But tragedy means that something is going to happen. What is happening to India’s oldest mountain range is not an accident and can’t be stopped. It happened because of planned government choices that see land as a financial asset and the environment as a negotiated annoyance.

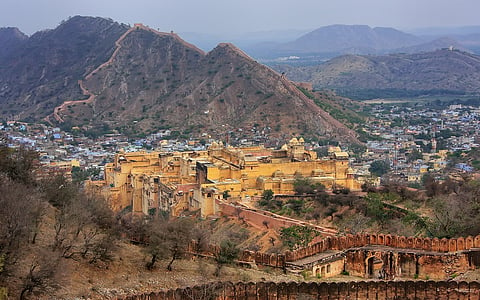

The Aravallis have been around for billions of years and are found in Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, and Delhi. They might not look very interesting, but they play an important role in the environment. They stop the Thar Desert from getting worse, fill up aquifers, keep the soil stable, and keep the temperature from getting too hot or too cold in northern India. So, their decline is not just a local problem. It changes the risk of climate change, the safety of water, and the health of millions of people.

Still, the Aravallis are still being treated like they are disposable.

When the hills became “open land”

Historically, the Aravallis have been put into groups that make them very weak. A lot of the range was called gair mumkin pahad, or revenue wasteland. This meant that the land lost its ecological value and the hills became “available” for administrative purposes. After forests lost their moral and legal weight, it was easier to mine, flatten, lease, and rezone these areas.

This classification did more than just let mining happen. It changed how state governments saw their work. As the economy grew, the Aravallis changed from biological infrastructure to reserve land banks. These are areas that can be used to make money, build more homes, and do infrastructure projects. The effects of this thinking can today be seen throughout Haryana and Rajasthan, as quarrying scars hill systems, wildlife corridors are disrupted, and groundwater levels fall year after year.

The courts spoke

The Indian courts have not been quiet about the Aravallis. Over the years, courts have repeatedly recognised how fragile the environment is and put limits on mining and building in sensitive areas. But clear court decisions have always been at odds with creative government work.

Instead of openly breaking court orders, state officials have relied on reinterpretation, such as changing the boundaries of forests, making the legal definition of “forest” narrower, or allowing activities through a series of permissions and exemptions. The result is the weakening of regulations without a formal repeal.

This pattern shows that there is a bigger problem with institutions: in India, environmental protection often only works as long as it doesn’t get in the way of development pipelines. Once it does, interpretation is the best way to dilute.

The real estate frontier

The Gurugram-Faridabad route has the most violence. The Aravallis are in the way of speculative urban growth and land that can be sold. Hills that developers used to think were impossible to build on are now seen as obstacles to growth.

Farmhouses, luxury homes, resorts, and access roads have all been moving up the hill, breaking up ecosystems without getting much attention. Most of the time, environmental impact assessments look at the damage done by one project at a time instead of all the damage done by many projects. Each clearance looks small. Together, they clear out whole landscapes.

It’s politically useful to destroy things little by little. Even though none of the projects seem to be bad, the damage as a whole is permanent.

Compensatory afforestation as ecological fiction

Compensatory afforestation is one of the most common reasons given for this destruction. It says that planting trees in other places will make up for the loss of historic hill ecosystems. This reasoning is fundamentally flawed.

The Aravallis are not just flat areas with trees. They are geological formations that shape the climate, control the flow of water, and stabilise the soil. Their ecological functions are non-transferable. When plantation forces are treated as substitutes, ecology becomes accounting, which is just a way to trade numbers instead of services.

This myth lets damage happen while still making it look like everything is okay. It may look like forest cover is getting bigger on paper. Ecological resilience has broken down on the ground.

Climate stress changes everything

The extra pressure on the Aravallis couldn’t have come at a worse time. North India is going through a long period of heat waves, low groundwater levels, and bad air quality. The Aravallis are a very important barrier against all three.

Flattening them now will have long-term costs that are much higher than the short-term benefits of development. These costs include more energy needed for cooling, more money spent on public health, more water shortages, and a higher risk of disasters. But these costs are still hard to see when making a budget because they happen over time and across different groups of people.

This is where the Aravalli debate and climate policy come together. It shows that people still see climate risk as a problem that will happen in the future, not as a current policy problem.

A reflection of India’s environmental politics

The Aravallis tell a story that is common in Indian environmental governance. It’s easiest to leave behind landscapes that aren’t famous, like old mountains, dry woods, and scrublands. There are pieces of protection, enforcement is hit-or-miss, and accountability is spread out over departments that don’t work together very often.

Some ecosystems are irreplaceable, not because they are pristine, but because people depend on their quiet work.

Saving the Aravallis doesn’t mean stopping development. It requires accepting limits, which is something India’s political economy doesn’t like very much.

Not just a disagreement in the area

It’s not right to call the Aravalli debate a local environmental issue; it’s much more serious than that. It shows how India values land, deals with climate risk, and finds a balance between growth and the health of the environment.

The oldest mountains in India don’t get in the way of progress. They pay for it. If the state keeps treating them like replaceable land or important infrastructure, it will affect not only the future of a mountain range but also how trustworthy India’s environmental governance is.

Anusreeta Dutta is a columnist and climate researcher with experience in political analysis, ESG research, and energy policy

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth