Empathy, policy, and lessons from literature: remembering Munshi Premchand

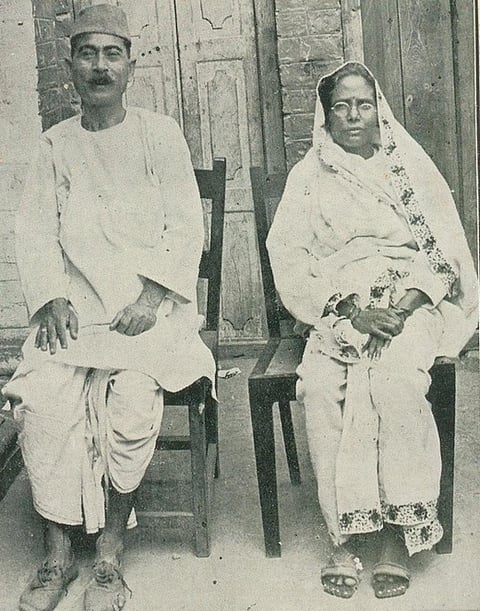

Munshi Premchand and his wife Shiv Rani Devi. Photo: Rashid Ahsraf via Wikimedia Commons

July 31 is Munshi Premchand’s birth anniversary. He was a prolific storyteller and author, steeped in the realism of everyday life. He wrote in Hindi and Urdu and painted vivid imagery of colonial India and its rurality with an unrelenting willpower, often with a glimmer of romance for better times. His remarkable writing career spanned 300 stories, 14 novels, and other anecdotes and works.

Premchand narrated the social ills prevalent in pre-independent India with a succinct clarity that has characterised the longevity of his craft. Short stories such as Sawa Ser Gehu, Poos Ki Raat, and the novel Godan, among others, depict exploitative conditions in society, many of which tragically continue to persist.

From the importance of livestock to rural communities, the vicious trap of indebtedness affecting farmers and agricultural labourers, the present-day policy concerns on crop insurance emanating from a farmer’s struggle to protect his fields from wildlife, and natural disasters, to grueling agricultural conditions and caste discrimination — his body of work implores us to look deep within our value system.

An all-encompassing search for sensitivity and compassion in human interactions dominates the essence of his writings. It makes them even more relevant in a world alienated and isolated because of machinated realities.

With a focus on kinship amidst economic hardship and social discrimination, there is an underlying search for idealism and humanitarian ethos. He demonstrates the social conditions of widows and their status within families (showed empathetically in Boodhi Kaaki and Jyoti, public utilities, and caste-based discrimination and consequent ostracisation in the society (classic Sadgati which was also made into a movie by Satyajit Ray in 1981, Thakur ka Kuan), are a few examples.

His stories teach us the importance of perseverance amid circumstances characterised by the coexistence of deprivation and aspiration. Panch Parmeshwar, a cult classic, demonstrates an unwavering faith and optimism despite the socioeconomic drudgery and brings to attention the focus on social justice and integrity.

The COVID-19-induced lockdown brought to light the large-scale apathy and the tyranny of distance between policymakers and people. The recent floods in Delhi, where the invisibility of urban poverty is again on display, also demonstrate the plight of the poor — which, while hitherto remaining obscure — suddenly becomes visible each time a catastrophe occurs.

In light of such contexts, policy conceptualisation can be imagined through a more empathetic lens by revisiting literature, movies, and other narratives in popular culture, as they are vital in providing us with social insights.

Management subjects like Design Thinking and Innovation already discuss the importance of ‘Empathy’ in business models and while developing prototypes of products, focusing on a human-centred lens in research.

Social sciences and public policy have addressed the relevance of inclusivity and sensitivity through research tools such as ethnography and participant observation drifting away from mere quantitative surveys. Qualitative research methods such as focus group discussions are paramount to skills such as listening and observing while studying social issues.

Therefore, stories by Premchand and other seminal works of literature can be used as pedagogical tools in policy making. Researchers and policymakers have begun to revisit literature and its relevance today in addressing social and public policy problems.

For instance, at the launch of the PM Ujjwala Yojana, the Prime Minister invoked Premchand’s story Eidgah. Eidgah is a heart-wrenching account of a little boy, Hamid, who watches his grandmother’s penury and plight while she makes rotis (flatbread) without tongs, because of which her fingers are burnt.

Hamid’s grandmother feels sorry about being unable to afford presents or celebrations for Hamid on the occasion of Eid. With almost no money on him, Hamid visits the Eid mela (fair) with his friends, and while his friends feast on delicacies and buy toys for themselves, Hamid buys a pair of tongs for his grandmother as an Eid present. The story resonates deeply with the Nari Shakti narrative of the Government of India, seeking to empower women by providing liquified petroleum gas connections under the Ujjwala Yojana and, therefore, the invocation.

Similarly, Boodhi Kaaki shows the intimate relationship between an almost abandoned and alienated great-grandmother and her great-granddaughter, Laadli. It captures the essence of aspiration, despair, and hunger and how older people are left at the mercy of circumstances and fate.

Laadli comes to the rescue of her great-grandmother while stealing food for her and feeding her. In the middle of a family function, where delicacies are being cooked, Boodhi Kaaki dreams of food and wants to feast on the puris (unleavened deep fried bread), mithais (sweets), and pakwaans (snacks) meant for a pre-wedding function.

However, the story ends with Kaaki fending for herself. Sitting next to the pile of thrown plates, she is seen enjoying the leftovers from the function, satiating her impending hunger and thirst for delicious food. This aspiration for food and the melancholia therein owing to poor conditions and the otherwise contradictions of life is also captured in Kafan.

In this context, it must be noted that with a growing corporatised ‘silver economy’ and India’s senior citizen population predicted at 319 million in 2050, merely gated infrastructural communities with robotic facilities may not solve the burgeoning social crisis of elderly neglect. Intimate social interactions, time with family, careful observations of what older people want, and making memories are essential to geriatric care.

In Jyoti, a sensitive rendition, Premchand focuses on abandonment and the consequent alienation of widows, the relationship a widow shares with three of her children, and how she battles the insecurity of losing her eldest son to his love interest in the village.

Sometimes impolite but kind at heart, the story revolves around the life of Buti, the widow in the story. She is bitter at instances and is always cursing Mohan, her eldest son. Premchand beautifully captures the bitter-sweet relationship between Buti and her children and shows how, with love, understanding, and empathy, Buti’s heart melts for Rupaiya, Mohan's love interest.

The socioeconomic empowerment of widows is a central policy concern today. According to a report, there are 40 million widows in India. The rural hinterland sees these widows’ invisibility due to the grave farmers’ suicide problem. A revisit to such stories, therefore, can offer more humane policies.

The quest for literature and its applications in policy to make us more empathetic is essential as we race against time in a tech-enabled fast-paced world.

A meticulous read of Ganadevta by Tarasanker Bandhopadhyay and Joothan by Om Prakash Valmiki and other literary works will give us lessons on deconstructing poverty with a more compassionate lens.

Such literary marvels help us seek idealism in today’s age of mindless materialism and self-consumption. Encapsulating literature in pedagogy helps us gravitate toward cultural and societal ethos and invigorate our ethics.

In the era of ChatGPT and machine-based learning where organic skills of observation are fast depleting, policymakers and educators must revisit the literature and introduce it as a mandatory component in courses, curricula, and training programmes.

The above analysis is not exhaustive of all of Munshi Premchand's writings. The author is a public policy expert based in Delhi

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth