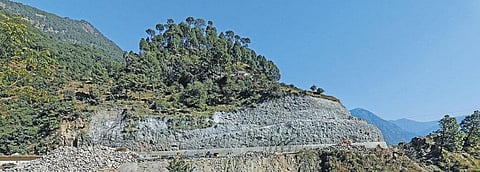

The colourful landscape of the Lesser Himalayas at Muni Ki Reti, on the outskirts of Rishikesh, does not paint a pretty picture. Fluorescent yellow of construction workers’ jackets dots the pale brown debris of the mountain in Uttarakhand. The greenery is replaced by the yellow and red of excavators and trucks. The mountain lay wounded and bare with the deep, sharp cuts which excavators have made to construct a road. The eyes adjust to seeing rows of hillocks formed by debris dumped by road construction trucks. Half uprooted trees hanging mid-air is a usual sight.

It’s not just road construction that has ravaged the mountain. Landslides are a recurring feature along Char Dham highways that lead up to Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. The Lesser Himalayas have a history of frequent landslides because of their recent origin and are, therefore, unstable. In 2003, a massive landslide damaged at least 100 buildings. As many as 3,000 people had to be evacuated. Heavy rains in 2016 killed scores of people in Pithoragarh and changed the landscape.

In such an ecologically sensitive area, the Centre decided to launch a Rs 12,000-crore project to improve road connectivity to the four revered Hindu pilgrimage sites in Uttarakhand. Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the construction of the Char Dham Mahamarg on December 27, 2016, as a tribute to those who died in the 2013 Kedarnath disaster.

The project will refurbish 900 km of the damaged highways with two lanes, 12 bypass roads, 15 big flyovers, 101 small bridges, 3,596 culverts and two tunnels. The roads will be widened at least 10 metres, and will be strong enough to withstand the harsh climate of the region. The improved highway circuit aims to ease traffic during the Char Dham Yatra, the backbone of Uttarakhand’s tourism and economy.

“This is an extremely fragile region,” says Ravi Chopra, director of People’s Science Institute, Dehradun. “You have to understand that the area forms the Main Central Thrust of the Lesser Himalayan region. This is where the Indian tectonic plate goes under the Eurasian Tectonic Plate,” he says. The phenomenon makes the region susceptible to earthquakes and landslides.

The Geological Survey of India corroborates this in its report prepared after the Kedarnath disaster. It states that road construction in mountains reactivates landslides as it disturbs the “toe of the natural slope of the hill.”

To assess the extent of the ecological damage that construction activity is causing, Down To Earth travelled 250 km on the Char Dham Mahamarg from Rishikesh to Gangotri. The evidence is apparent from Muni Ki Reti itself, the traditional gateway to the Char Dham pilgrimage.

A landslide here has breached the concrete wall built to keep the hill in place. “The landslide came during monsoon in July this year. The mountain was cut but not given a slope essential to sustain itself. When rains came, they brought down huge rocks and boulders. Fortunately, it happened early morning, so no one was hurt,” says a construction worker.

From Muni Ki Reti to Agrakhal, a small town some 30 km from Rishikesh, the ride is precarious. Houses just above areas where the mountain has been carved out balance dangerously on loose soil. A part of the telephone exchange office here stands isolated as the rest of it crumbled down along with the mountain beneath it.

“The road was widened in 1991 to take machines for the construction of Tehri dam on river Bhagirathi. It destabilised the slope. The mountain took 10 years to stabilise. Ever since work began in March last year, we are seeing the mountain side collapsing,” says Surendra Kandari, a resident of Agrakhal.

Between Rishikesh and Agrakhal, the road is as wide as 17 metres, says Himanshu Arora of non-profit Citizens for Green Doon. According to the Hill Road Manual of the Indian Road Congress, roads in this area should not be wider than 8.8 metres. “The construction is destined to cause a disaster,” he says.

Isolated at Agar

Just about three kilometres uphill, residents of Agar village in Narendra Nagar district have a peculiar problem. Road construction has left the village of around 150 households with no access to the world. The only road connecting the village to the main road, some 20 metres down the mountain, has collapsed. This correspondent walked up a slim kuchcha road, just about enough for one person, to reach the village. “I have to sell my buffalo, but there is no way I can take the buffalo to the buyer downhill. It’s not just us stuck on this crumbling hill, our cattle are also trapped,” says resident Bhag Singh Rawat.

Huge cracks have appeared on his house. The hill, along with the house, is slowly sliding down. “I went to the district magistrate and the tehsildar asking for help. They came, inspected the situation and assured me that something will be done. Four months later, the situation is the same,” he says.

“The mountain here was cut to widen the road in March, 2018. In July, a large portion of the mountain fell. A road and our agricultural fields collapsed along with it,” says Raichand Singh Rawat. The state government gave him compensation for the land acquired for construction, but he received nothing for the farmland he lost due to the landslide.

“I had 150 sq m of land where I grew ginger. The government took 80 sq m of this for road construction. The rest of the field collapsed on July 14. My ginger crop, for which I had taken a loan of Rs 35,000 loan, is all gone,” he says.

No compensation, no EIA

Construction work has not started in full swing at Khadi village, which borders Tehri district. The process of acquisition is ongoing. “I was told by the tehsildar in January last year that title holders will get compensation for the land they give,” says resident Balbir Singh Tadiyaal. “Later, the official said only the structure built on it will be compensated for. When I went to meet him in October, he said title holders will not be compensated for anything. I have only one piece of land, and have built a hotel on it. What will I do if the land is taken away?”

Amitabh Singh Rawat does not own land, nor is he a title holder. But he has planted a good number of mango trees in Khadi’s valley. Bharat Construction, the company making the road on this stretch, has dumped debris from a landslide into the valley. All the mango trees and vegetation growing around it are now buried under debris. Rawat has not received any compensation.

As many as 25,300 trees have been cut and 373 hectares of forestland diverted for Char Dham Mahamarg. “We only know the number of trees that were cut for the project. No one knows how many trees were lost in landslides,” says Arora. “We had no idea that it was going to be such a massive construction work”. Arora’s non-profit is one of the petitioners in a case filed with the National Green Tribunal (NGT) against the construction work. The petitioners have asked why the Uttarakhand government started the mega construction project in an ecologically fragile zone without conducting an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study.

Five kilometers above Khadi, Bidon Khankar Marg, the only motorable road in Tipli village, has developed cracks after a kuchcha road near it collapsed in landslides. On some stretches, the road has sunk in. “I went to the district magistrate to complain about the road and get it repaired. He told me to talk to the additional district magistrate, who in turn, said we should get the road built using our village funds,” says Phuldas Dhandiyal, former pradhan of Tipli.

Uttarkashi, however, is a pleasing sight. Construction work has not started here because of the NGT petition. The Border Road Organisation has marked many deodar trees on this stretch for felling, but NGT has given a stay order after Birendra Singh Matura filed a petition against it (see ‘Petitions against project’).

The road from Uttarkashi to Gangotri comes under the Bhagirathi Eco-Sensitive Zone (ESZ). Development activity here can take place only if it complies with the zonal masterplan of ESZ. In fact, the Uttarakhand forest department has imposed fine of Rs 5 lakh on BRO, one of the government bodies constructing the road, for illegally dumping debris in the Bhagirathi. “I am not against the road. It will help us economically. But it should be done taking into account the environmental impact,” says Birendari Nautiyal, who has a teastall in Bhatwari, a small village some 70 km from Gangotri.

“The government is imposing a project disregarding the ecological concerns of the area. Making a road is fine, but it should be done keeping in mind its ecological implications. Else, it won’t be long before another disaster hits Uttarakhand,” says a resident of Uttarkashi Jaihari Srivastav.

| Petitions against project

However, when the new chairperson Adarsh Kumar Goel took charge on June 9, he ordered rehearing of the case by a four-member bench. The petitioners challenged this in the Supreme Court, which ordered the original bench to hear the case. On September 26, NGT gave its clearance for the project and ordered the formation of a committee comprising members from the Wadia Institute of Geology in Dehradun, Govind Ballabh Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment and Sustainable Development in Almora, National Institute of Disaster Management, Central Soil Conservation Board, Forest Research Institute in Dehradun and forest officials from Uttarakhand, to oversee the project. This clearance was struck down by the apex court on October 22. The government interpreted this as a go-ahead for the construction work. In May 2017, another petitioner, Birendra Singh Matura filed a case against the Uttarakhand government in NGT for violating the Bhagirathi Eco-Sensitive Zone (ESZ). The Bhagirathi ESZ stretches from Uttarkashi to Gangotri. The case was disposed of by NGT, which ordered the authorities should comply with the rules. |

(This article was first published in the 1-15th January 2019 issue of Down To Earth under the headline 'Fault lines in expressway')