Scientists say urban sewage is helping dangerous bacteria develop resistance to common antibiotics

Study finds hospital-linked pathogens and drug residues in wastewater and rivers

Researchers warn weak regulation and poor sewage treatment are worsening the public health risk

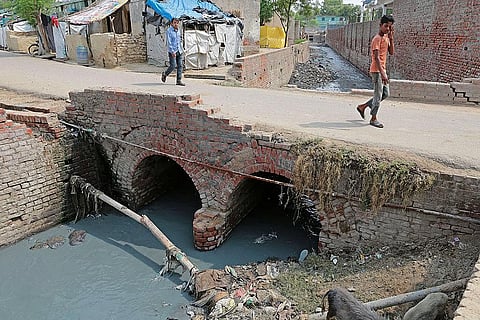

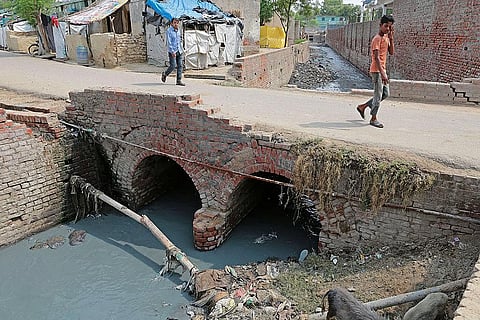

Sewage flowing through Indian cities is carrying pathogenic bacteria linked to hospitals and is helping drive resistance to commonly used antibiotics such as azithromycin, according to new research. Scientists say traces of antibiotics in drains and sewers are effectively “training” bacteria to evade treatment, raising the risk that widely used drugs will become ineffective. The findings suggest antibiotic resistance is no longer confined to hospitals but is spreading through urban wastewater systems and into rivers.

The study, Antibiotic contamination and antimicrobial resistance dynamics in the urban sewage microbiome in India, has been published in the journal Nature.

Researchers found that sewage in Indian cities has become a breeding ground for dangerous bacteria, many of which resemble pathogens responsible for hospital-acquired infections. Antibiotic residues entering sewage systems — from hospitals, households and other sources — allow bacteria to develop and share drug-resistant traits.

The study found that the Yamuna River is receiving antibiotic-contaminated wastewater from nearby urban centres, including hospital effluents. Open drains, peri-urban sewage channels and untreated hospital waste often flow directly into the river, posing health risks to communities downstream.

Some antibiotics, including amoxicillin, were detected in sewage at concentrations high enough to encourage gene exchange between bacteria, enabling them to pass drug-resistant traits to one another.

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) are genes that give bacteria the ability to evade the effects of antibiotics. These genes help bacteria neutralise the drug, expel it from the cell, or tolerate its effects. Worryingly, bacteria can share these genes, especially in environments like sewage, making even common bacteria more susceptible to drug resistance and potentially dangerous.

The researchers found that most ARGs detected in sewage were linked to commonly used drug classes such as beta-lactams and aminoglycosides. Notably, aminoglycoside resistance genes were found to be 50 per cent more prevalent in sewage than in hospital samples.

This suggests resistance genes are entering sewage not only from human waste but also from poultry, fisheries and agricultural sources.

To assess how widespread resistant bacteria are and how they spread within cities, scientists repeatedly collected sewage samples from five community sites and two hospitals in Faridabad, a densely populated industrial city.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that bacteria in Faridabad’s sewage shared the same genetic sequence types as pathogens causing hospital infections globally between 2019 and 2023. These included strains of Escherichia coli (ST167 and ST410), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ST15 and ST37) and Acinetobacter baumannii (ST2).

The findings indicate that bacteria circulating in wastewater are genetically similar to those responsible for serious clinical infections.

The research team analysed hundreds of sewage samples collected from six Indian states between June and December 2023. They tracked antibiotic residues, resistance genes and microbial communities in both community sewage and hospital wastewater.

In total, they detected residues of 11 widely used antibiotics from seven drug classes. Traces of kanamycin were found in 67 per cent of samples, while azithromycin was present in 56 per cent, indicating widespread use and environmental release.

The study found high levels of resistance genes — including mphA, mphE and msrE — which neutralise or expel azithromycin from bacterial cells. Another gene, ermB, which alters the drug’s target site, was particularly common in hospital-associated wastewater.

Overall, the researchers identified 170 different resistance genes conferring resistance to 16 antibiotic classes.

To assess the scale of resistance, scientists used rapid detection strips, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry to measure antibiotic residues, metagenomic sequencing to identify bacteria and their genes, and culturomics to grow bacteria in the laboratory.

This process yielded 964 bacterial isolates. Of the 681 tested against 32 antibiotics from 10 drug classes, nearly 94 per cent were resistant to more than 10 antibiotics.

Genome sequencing of 305 bacterial samples revealed resistance genes across 16 bacterial families and 31 species, including pathogens that cause serious human infections such as E coli, K pneumoniae, Morganella morganii and Enterococcus faecium.

“We show a direct correlation between antibiotic concentrations in sewage and the abundance of antibiotic-resistant pathogens,” said Bhabatosh Das, a senior author of the study and microbiologist at the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, in comments published in the journal Nature India.

“We are seeing active circulation between sewage and hospitals,” Das stated. “Sewage serves as a reservoir for the emergence and dissemination of XDR pathogens.”

Extensively drug-resistant, or XDR, pathogens are bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics, leaving few treatment options.

“AMR genes are expected in sewage,” said Farah Ishtiaq, who leads disease ecology and environmental surveillance at the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society, “but linking them directly to antibiotic concentrations strengthens the case for environmental surveillance — especially in a country with weak regulation of antibiotic use.”

The researchers also stressed the need for an India-specific reference database for antibiotic resistance genes, arguing that the country’s unique microbial ecology and resistance pathways require locally grounded monitoring to track how resistance evolves and spreads.