The big transition that was Project Tiger

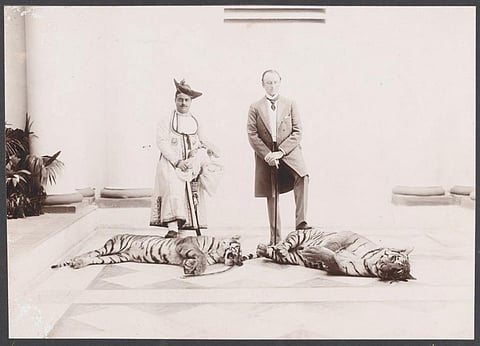

Lord Curzon and Maharaja Madhavrao II Scindia of Gwalior, 1911. Photo: National Army Museum

The world celebrated International Tiger Day on July 29, 2022. This year was the deadline decided in the 2010 Global Tiger Summit in Russia. Then, it had been decided that tiger numbers should be doubled. Nepal has done it according to new figures it released July 29. India too is not in a bad spot.

In fact, it is the four south Asia countries — India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan — that are now home to 76 per cent of the global tiger population, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Russia too has not been performing badly. It is only southeast Asia that has touched rock bottom. More on that later.

If there is one thing that we must thank for our tiger numbers, it is Project Tiger. The landmark project to save the Bengal tiger was launched in April 1973. Next year, India will mark 50 years of it.

Environmental historian Mahesh Rangarajan noted at a recent event titled Two Centuries of Hunting and Five Decades of Conservation in India organised by WWF-India, WCS-India, and Panthera, New York, that Project Tiger “was a transition from a very big game-centred view of nature, certainly among imperial British officials, Indian princes and foresters towards a more inclusive idea of conservation.”

Indeed, the circumstances that led to Project Tiger and the landmark Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, are rooted in the so-called ‘Shikar Era’ of the 19th century.

Tigers in British India were seen as an impediment to the spread of cultivation. Much of the draught power came from bulls and bullocks. And tigers and leopards were seen as harmful since they attacked draught cattle, according to Rangarajan.

They were also seen as a threat to human life. “It was also a notion of imperial conquest, certainly in British India, that you tried to eliminate many these large animals to establish the power of the (British) sovereign in India,” he noted.

Up to 1925, there were regular rewards given out by all provinces for killing, not only tigers but various other carnivores. From the 1870s to the 1920s, some 1,500-1,600 tigers were killed every year just for rewards.

All that changed with the advent of Project Tiger. The period from 1969 to 1972 is a period of what we would today call environmental awakening. The tiger became both the symbol and index of that awakening, according to Rangarajan.

The tiger became a symbol at this time of a type of patriotism. It began to be called the Indian Tiger in 1972. It became the National Animal.

“When asked why it was the National Animal, the chair of Project Tiger Karan Singh said it was found in 11 of 16 Indian states. So it would be symbol of unity in diversity,” Rangarajan said.

MK Ranjitsinh, who drafted the WLPA, had recounted how the Act and Project Tiger came about in his book A life with wildlife which was published in 2017. He was also present at the recent event and again recounted interesting anecdotes from the time.

“Luckily, we had a prime minister who was interested in conservation. The IUCN Conference of 1969 in Delhi was Indira Gandhi’s first exposure to the issue. But she did not have direction yet,” he says.

Mrs Gandhi had called a meeting in September 1971 to say what could be done about nature conservation. Many in that meeting said wildlife was a state subject and the Centre could not legislate any law related to it.

When his turn came, Ranjitsinh said the Centre could indeed legislate, provided two states empowered it to do so and then applied it to them and others who adopted the legislation.

“Karan Singh asked which state would give the Centre the power. Mrs Gandhi turned to him and said I will write to the states and she did. Would you believe it that before I finished drafting the WPA and before it was cleared, 18 states including one non-Congress one had passed that legislation. They did not even know what the legislation was. That would not happen now,” he recalled.

India is indeed fortunate that Project Tiger succeeded. Other tiger range regions have not been so fortunate. Southeast Asia, referred to in the earlier part of this writeup, was in the news recently, with the IUCN announcing that the tiger had become extinct in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

Having said that, the next 50 years will bring new challenges with them.

Sonali Ghosh, Chief Conservator of Forest (Research, Education and Working Plan) Government of Assam, who attended the event, said, “We have to invest in human resources and also have to respect the green warriors who are not only protecting the forest and animals but are also preventing human-animal conflicts. There should be respect for diversity of governance.”

Rangarajan has pointed to the disparities in tiger range states in north, south and north-eastern India.

“Tamil Nadu’s agriculture GDP is just 12 per cent. There are four tiger reserves in the state. But there will be no demand for fuel wood. The population is not only urban, wage rates are high,” he said.

In North India, the sharpness of the conflict is high. The agricultural productivity and wage rates are lower and the number of people who depend on the forest and land is also larger.

“The gap between the administration and some of the sections can be bitter or even sharp. The North East is a completely different situation,” he said.

He also noted that one of the problems in conservation today is money. “In half a dozen tiger reserves, there is enormous wealth being generated for tourism operators. The Tiger Task Force had suggested that 30 per cent of it should be divided locally. But that has not happened in India,” he said.

“Can we have a different partnership with the citizen science community? That partnership has to go well beyond the tigers. If it is to succeed, it must be part of a much larger transformation. In the next 50 years, that will be the challenge: How do you craft such citizen science community partnerships?”

Is India game?