It’s too early to say whether Australia is in for a scorching summer

The Northern Hemisphere summer has brought one extreme event after another — from heatwaves to wildfires and floods. It comes as the world likely heads into an El Nino pattern, which brings a higher chance of hot, dry weather in much of Australia.

So is the weird northern summer a portent of what Australia can expect in a few months?

The extremes in the Northern Hemisphere are linked to persistent weather patterns which allow heat to build in some places and rain to continue in others. On top of this, human-caused climate change is raising temperatures to new heights.

It’s too early to say whether Australia is in for a scorching summer. The predicted El Nino is a worry, but doesn’t guarantee the record-smashing heat we’re seeing in parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

Having said that, continued global warming will bring more record-high temperatures in Australia. So we must remain on high-alert — and ramp up reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Wild weather in the Northern Hemisphere at this time of year is to be expected. However, recent extremes are off the charts.

Major heatwaves are underway in North America, Europe, North Africa and Asia. In California’s Death Valley, temperatures on Sunday reached 53.3 degrees Celsius. Parts of Italy were expected to reach 45℃ on Tuesday and later in the week could approach Europe’s hottest temperature on record: 48.8℃.

China provisionally reached 52.2℃ on Sunday, shattering the previous record for the country by more than 1.5℃.

Meanwhile, wildfires are tearing through Canada, Greece and Spain, destroying properties and forcing evacuations.

So what’s causing these simultaneous heatwaves across multiple regions? They’re all linked to high-pressure weather systems that are “blocking” or deflecting oncoming low-pressure systems (and associated clouds and rain).

These low-pressure systems have moved to other areas and caused extreme rainfall and flooding. Flooding in South Korea has left 40 people dead and destroyed critical infrastructure. Vermont, in the northeast United States, was also flooded after up to two months of rain fell in a few days.

Alarmingly, the atmospheric patterns driving the extremes in the Northern Hemisphere appear to be getting more common under climate change. On top of this, human-caused global warming is greatly increasing the chance of record-breaking extreme heat events and concurrent heatwaves across many regions.

All this begs the question of what might be coming Australia’s way this summer.

There’s one factor working in our favour: the particular atmospheric pattern bringing extremes to the Northern Hemisphere isn’t replicated in the Southern Hemisphere, because we have more ocean and less land.

However, Australia does experience its own “blocking” high pressure patterns which also bring major heatwaves and extreme rain events. Unfortunately we can’t predict these months in advance.

El Nino is a little more easily predicted. Currently, the tropical Pacific Ocean is trending towards El Nino conditions, as waters off the west coast of Ecuador and Peru continue to warm.

El Nino is part of a natural fluctuation in the Earth’s climate system which typically lasts for the best part of a year. It raises the chance of a warmer and drier spring in Australia.

Some meteorological agencies say an El Nino has already arrived. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology is holding off on a declaration, for now. That’s because while the Pacific has fallen into an El Nino pattern, the atmosphere hasn’t yet followed.

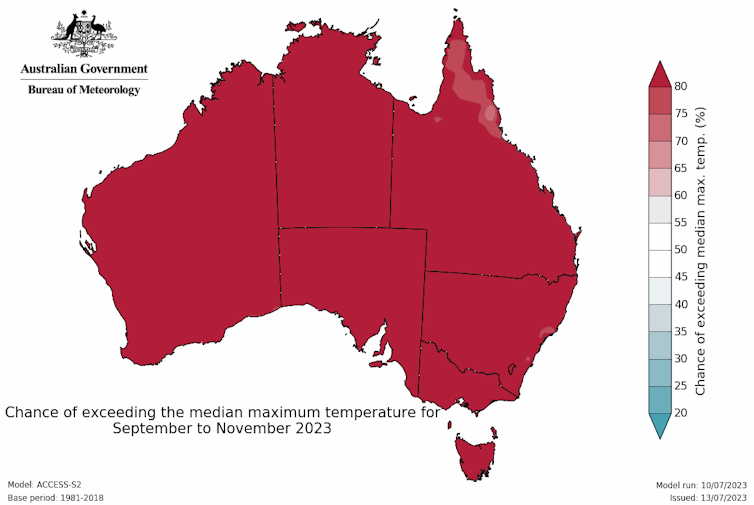

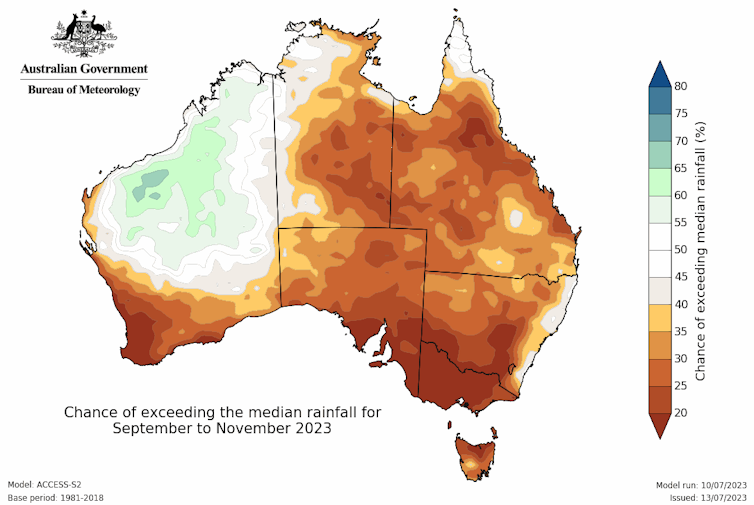

But the bureau still puts the likelihood of an El Nino at 70 per cent and forecasts warmer and drier conditions across much of Australia from August to November.

The extreme weather in the Northern Hemisphere isn’t strongly related to the developing El Nino. But by the time Australia’s summer arrives, we’ll likely see El Nino’s effects in the weather.

What’s more, another driver of Australia’s climate, the Indian Ocean Dipole, is likely to enter a positive phase in coming months.

This phase is associated with warmer seas in the west Indian Ocean. This leads to fewer low pressure systems, on average, over southeast Australia and less atmospheric moisture over most of the continent. This would likely suppress winter and spring rainfall over much of Australia and exacerbate an El Nino’s drying effect.

Not all El Nino and positive Indian Ocean Dipole events bring warm, dry weather. And there isn’t a strong relationship between the magnitude of an El Nino and the lack of rain in Australia. But these background climate conditions raise the chance of a warmer and drier spring.

We can’t yet predict if Australia will swelter this summer. But an El Nino increases the chance of hotter and drier summer conditions, with more heatwaves and a greater frequency of weather conducive to fire spread.

Of course, all this comes on top of human-driven global warming. In Australia, land areas have already warmed by 1.4℃ over the past century and the cool summers common before 1980 are now far less likely.

In fact, even if global warming is limited to well below 2℃, historically hot summers in Australia will become common.

The Northern Hemisphere’s current extreme weather and predictions of hotter summers in Australia, are all evidence of humanity’s fingerprints on Earth’s climate. This should spur urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Because if global warming continues, Australia is certain to be hit by more record-breaking heat events — and that is not something we want to experience. ![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.