Time spent at fish camps is critical for many Alaska Indigenous cultures & kids are missing out on that experience

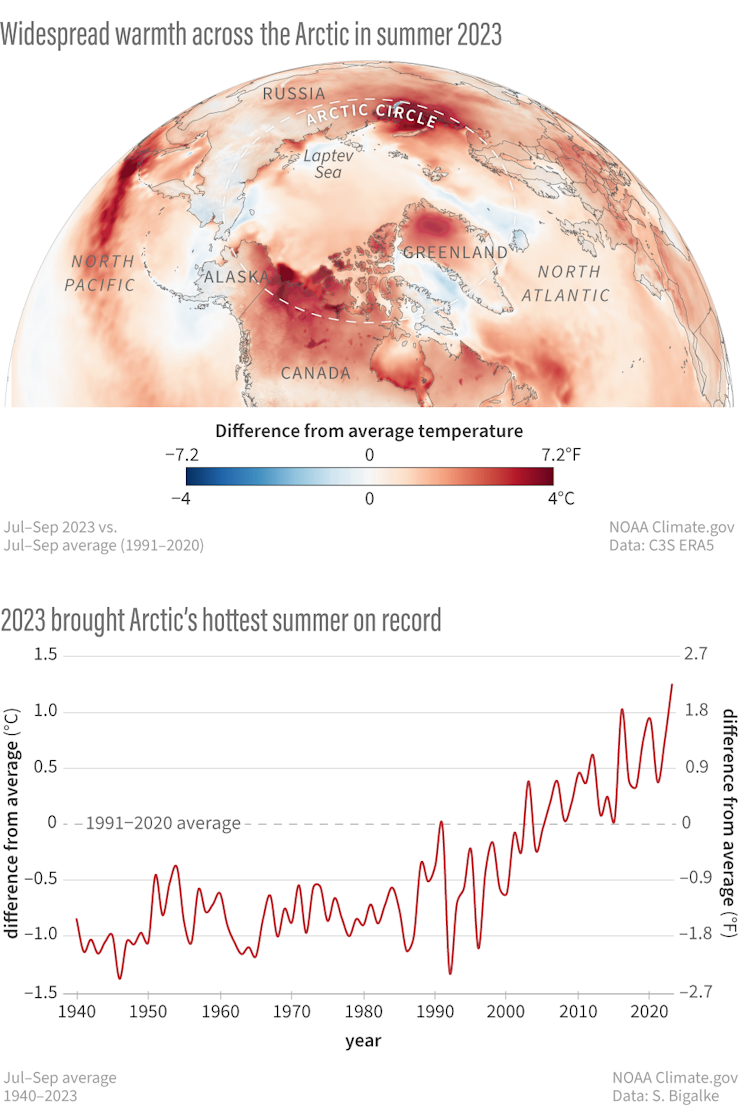

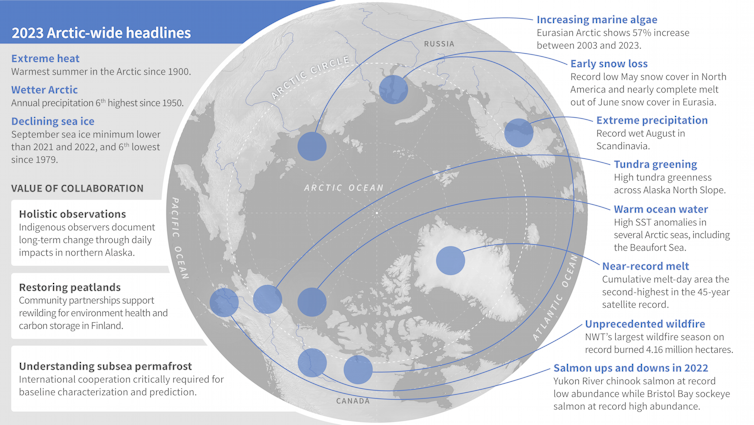

The year 2023 shattered the record for the warmest summer in the Arctic, and people and ecosystems across the region felt the impact.

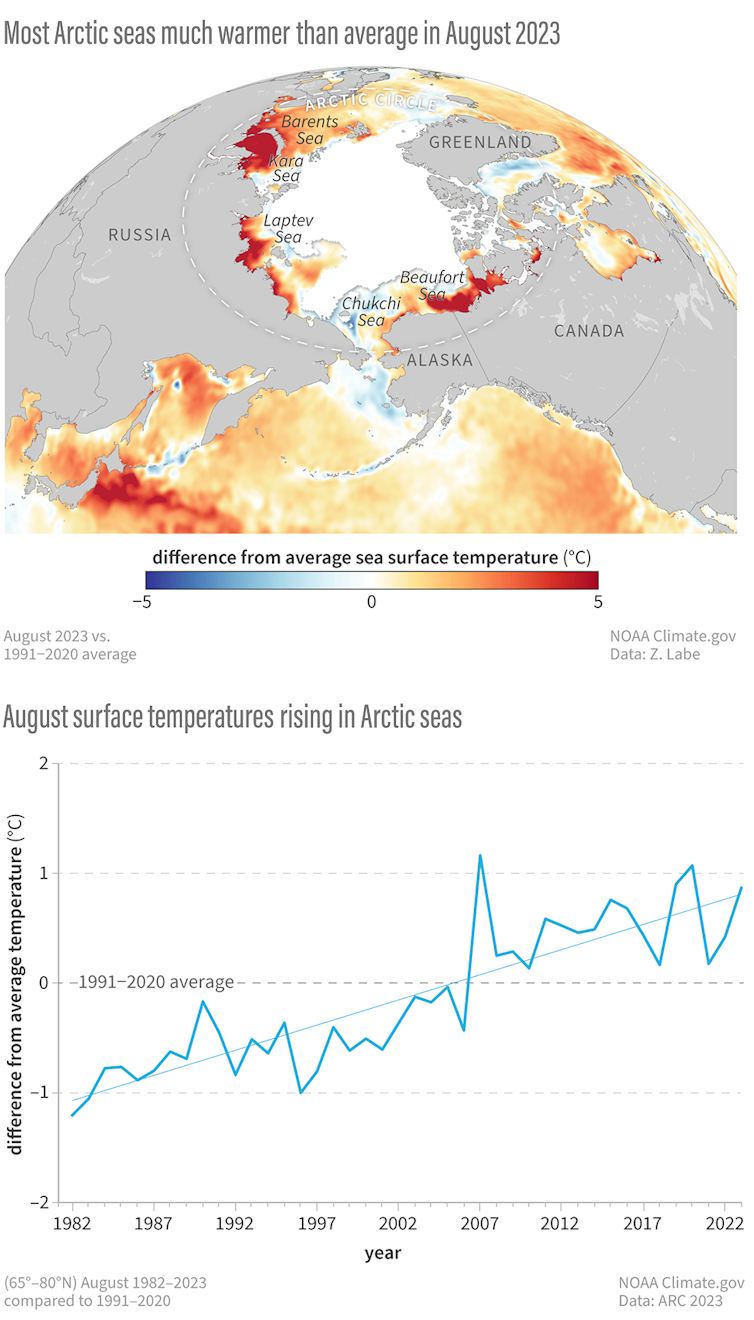

Wildfires forced evacuations across Canada. Greenland was so warm that a research station at the ice sheet summit recorded melting in late June, only its fifth melting event on record. Sea surface temperatures in the Barents, Kara, Laptev and Beaufort seas were 9 to 12 degrees Fahrenheit (5 to 7 degrees Celsius) above normal in August.

While reliable instrument measurements go back only to around 1900, it’s almost certain this was the Arctic’s hottest summer in centuries.

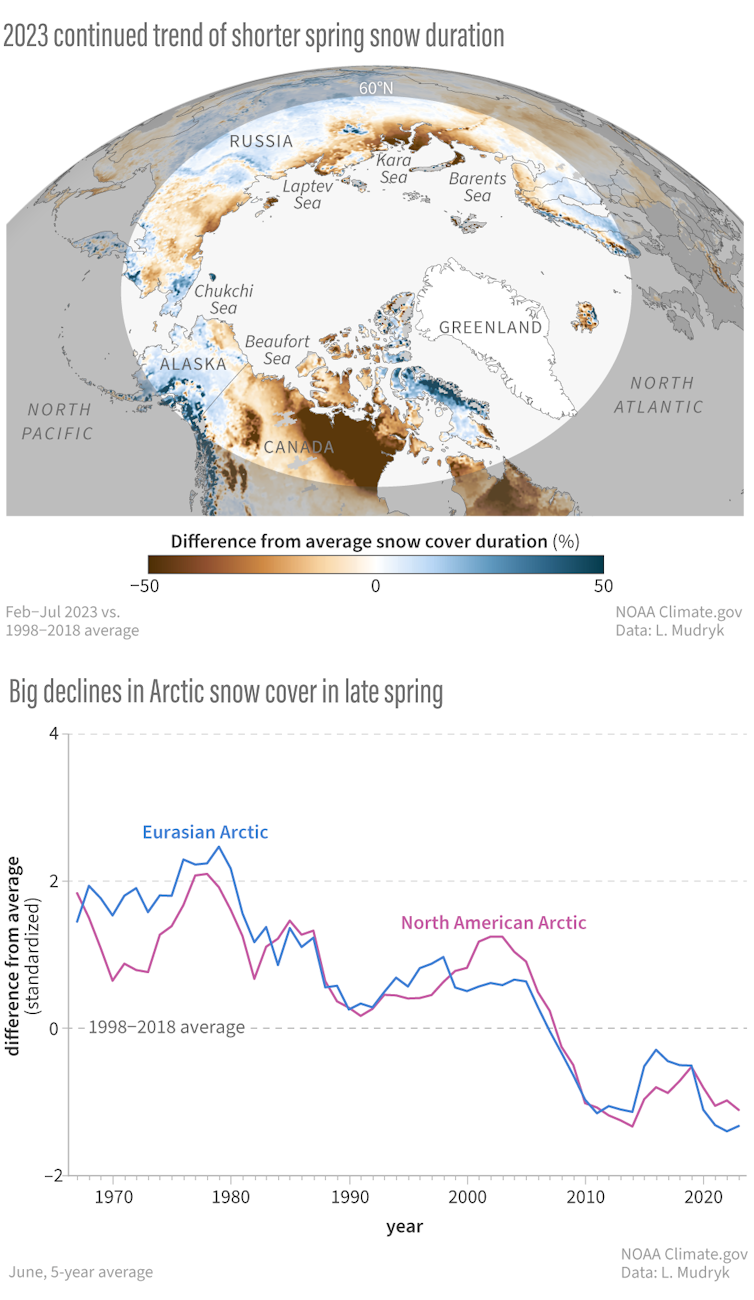

The year started out unusually wet, and snow accumulation during the winter of 2022-23 was above average across much the Arctic. But by May, high spring temperatures had left the North American snowpack at a record low, exposing ground that quickly warmed and dried, fueling lightning-sparked fires across Canada.

In the 2023 Arctic Report Card, released Dec. 12, we brought together 82 Arctic scientists from around the world to assess the Arctic’s vital signs, the changes underway and their effects on lives across the region and around the world.

In an area as large as the Arctic, setting a new temperature record for a season by two-tenths of a degree Fahrenheit (0.1 degrees Celsius) of warming would be significant. Summer 2023 – July, August and September – shattered the previous record, set in 2016, by four times that. Temperatures almost everywhere in the Arctic were above normal.

A closer look at events in Canada’s Northwest Territories shows how rising air temperature, sea ice decline and warming water temperature feed off one another in a warming climate.

The winter snow cover melted early across large parts of northern Canada, providing an extra month for the Sun to heat up the exposed ground. The heat and lack of moisture dried out organic matter on and just below the surface; by November, 70,000 square miles (180,000 square kilometers) had burned across Canada, about a fifth of it in the Northwest Territories.

The very warm weather in May and June 2023 in the Northwest Territories also heated up the mighty Mackenzie River, which sent massive amounts of warm water into the Beaufort Sea to the north. The warm water melted the sea ice early, and currents also carried it west toward Alaska, where Mackenzie River water contributed to early sea ice loss along most of Northeast Alaska and to increased tundra vegetation growth.

Similar warmth in western Siberia also contributed to quickly melting sea ice and to high sea surface temperatures in the Kara and Laptev seas north of Russia.

The Arctic’s declining sea ice has been a big contributor to the tremendous increase in average fall temperatures across the region. Dark open water absorbs the sun’s rays during the summer and, in the autumn, acts as a heating pad, releasing heat back into the atmosphere. Even thin sea ice can greatly limit this heat transfer and allow dramatic cooling of air just above the surface, but the past 17 years have seen the lowest sea ice extents on record.

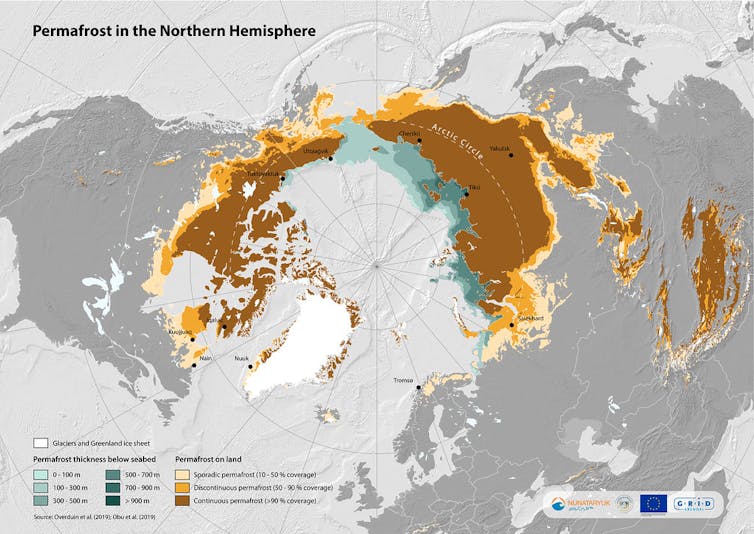

The report includes 12 essays exploring the effects of climate and ecosystem changes across the Arctic and how communities are adapting. One is a wake-up call about the risks in subsea permafrost, a potentially dangerous case of “out of sight, out of mind.”

Subsea permafrost is frozen soil in the ocean floor that is rich in organic matter. It has been gradually thawing since it was submerged after Northern Hemisphere ice sheets retreated thousands of years ago. Today, warmer ocean temperatures are likely accelerating the thawing of this hidden permafrost.

Just as with permafrost on land, when subsea permafrost thaws, the organic matter it contains decays and releases methane and carbon dioxide – greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming and worsen ocean acidification.

Scientists estimate that nearly 1 million square miles (2.5 million square kilometers) of subsea permafrost remains, but with little research outside the Beaufort Sea and Kara Sea, no one knows how soon it may release its greenhouse gases or how intense the warming effects will be.

For many people living in the Arctic, climate change is already disrupting lives and livelihoods.

Indigenous observers describe changes in the sea ice that many people rely on for both subsistence hunting and coastal protection from storms. They have noted shifts in wind patterns and increasingly intense ocean storms. On land, rising temperatures are making river ice less reliable for travel, and thawing permafrost is sinking roads and destabilizing homes.

Obvious and dramatic changes are happening within human lifetimes, and they cut to the core of Indigenous cultures to the point that people are having to change how they put food on the table.

Western Alaska communities that rely on Chinook salmon saw another year of extreme low numbers of returning adult salmon in 2023, scarcity that disrupts both cultural practices and food security. Yukon River Chinook have decreased in size by about 6% since the 1970s, and they’re producing fewer offspring. Then, in 2019, the year when many of this year’s returning Chinook salmon were born, exceptionally warm river water killed many of the young.

The returning Chinook salmon population has been so small during the past two years that fisheries have been closed even for subsistence harvest, which is the highest priority, in hopes that the salmon population recovers.

The inability to fish, or to hunt seals because the sea ice has thinned, is not just a food issue. Time spent at fish camps is critical for many Alaska Indigenous cultures and traditions, and kids are increasingly missing out on that experience.

As Indigenous communities adapt to ecosystem changes, people are also working to heal their landscapes.

In Finland, an effort to restore damaged reindeer habitat in collaboration with Sámi reindeer herders is helping to preserve their way of life. For many decades, commercial logging was allowed to tear up hundreds to thousands of square miles of reindeer peatland habitat.

The Sami and their partners are working to replant turf and rewild 125,000 acres (52,000 hectares) of peatlands for reindeer grazing. Degraded peatlands also release greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change. Keeping them healthy helps capture and store carbon away from the atmosphere.

Temperatures in the Arctic have been rising more than three times faster than the global average, so it’s not surprising that the Arctic saw its warmest summer and sixth warmest year on record. The 2023 Arctic Report Card is a reminder of what’s a stake, both the risks as the planet warms and the lives and cultures already being disrupted by climate change.![]()

Rick Thoman, Alaska Climate Specialist, University of Alaska Fairbanks; Matthew L. Druckenmiller, Research Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado Boulder, and Twila A. Moon, Deputy Lead Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.