Societies operate on principles more fundamental than keeping score. For publicly traded companies, one of these is the obligation of transparency owed to its shareholders

Liability for contributing to climate change is fair in principle, politically controversial, and frequently looks like an almost impossible technical challenge.

On top of the most complex systems modelling feat of all time, it demands demonstrable linkages between mounting systemic risk and decisions made by individual firms. Every element of a climate-economy model multiplies uncertainty — neatly quantified estimates of damages seem unlikely to see a courtroom any time soon.

Fortunately, societies operate on principles more fundamental than keeping score. For publicly traded companies, one of these is the obligation of transparency owed to its shareholders.

Specifically, the State of New York in the United States believes that section 352 and section 63 (12) of its General Business Law oblige an oil company (ExxonMobil Corp) to accurately disclose to its shareholders the risk that its assets (oil) could be stranded (left un-extracted) owing to forthcoming climate regulations.

The State filed a suit before the State Supreme Court in October 2018, and is set to go to trial this week. It contends that:

Effectively, ExxonMobil projected in public an air of confidence that its assets would continue to gain value even in a world with a high carbon price. In contrast, its actual method to project future oil demand — details of which were not available to the general public — allegedly used a much lower carbon price (or did not use one at all).

From a policy perspective, this kind of deception keeps money in a carbon-intensive industry, and obstructs a desperately needed energy transition.

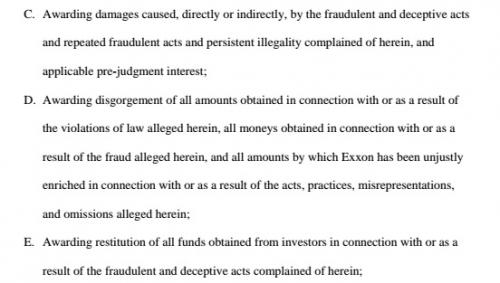

This broader concern is not the core of New York’s suit — it is narrowly concerned with the reporting obligation. Based on that argument, the State seeks financial relief for allegedly misled shareholders.

This argument for liability is based primarily on a non-quantitative baseline — the principle that, for certain types of risk, a corporation must maintain consistency between its inner monologue and its public posture.

This, in turn, rests on the intuition that while people within such corporations are usually quite alive to the risks their business faces, corporate leadership simply chooses not to be held accountable for their business model.

This is a generally sound intuition. Take, for example, the alleged response of Exxon management to its own planners’ concerns regarding an asset in Alberta, Canada.

A parallel effort is underway in Massachusetts. A civil investigative demand by the State of Attorney General to ExxonMobil has been met with a slew of ‘pre-litigation’ litigation, ending with the US Supreme Court deferring to the Attorney General.

That action is behind New York’s on timeline, but broader in scope — it relies on exposés by American news organisations establishing that ExxonMobil scientists knew about the societal risks associated with fossil fuels in the 1970s.

ExxonMobil’s cynical, measured response to this discovery is captured in a new multi-university report by communication researchers in the US, titled America Misled: How the Fossil Fuel Industry deliberately misled Americans about climate change.

It describes how corporate communications mounted a paid advertorial campaign in newspapers, sowing doubt about climate science itself, while the company’s scientists continued to publish realistic, nuanced analysis in academic journals.

The discrepancy is quantifiable, and holds up across all elements of the climate crisis — whether it is human-caused, the seriousness of impacts, and its solvability.

Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes 2017. Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977—2014). Environ. Res. Lett.12 084019 (Supran and Oreskes are also co-authors on the America Misled report)

If these assessments hold up in court, some companies will face demands for a lot more than transparency. Considering the aggressive globalisation of oil, these demands are unlikely to be contained within the US.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.