India has more elderly people than ever before. Most of them have little social security and cannot afford healthcare. While the government seems ill-prepared to provide them care, private players are rushing to offer expensive facilities and services. Jyotsna Singh reports

Elderly & lonely

Living to a ripe old age should be a cause for celebration. Alas, it was not so for Usha John, once a sprightly, hard-working and fiercely independent IAS officer. After retirement, John lived in her bungalow in the upmarket Hauz Khas of Delhi, aided by a few housekeepers. But over the years, they deserted her. “In March, I received a call from one of her neighbours who informed that they had not seen any activity in John’s house for a long time,” says Mathew Cherian, chief executive of HelpAge India, a non-profit working for the rights of the elderly. “When we visited her house, we discovered a frail figure.” She was barely 19 kg. Cherian rushed her to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), where the doctors informed that she had hardly eaten anything for two to three months and was suffering from cancer. The 85-year-old spinster died in the hospital a month later. Some relatives of her sister, who lives in Mumbai, came to complete hospital formalities.

Unlike John, 82-year-old Urmila Devi has two sons who are doing quite well for themselves. Yet she is living out her dotage in an old-age home in Kanjhawala in north-west Delhi. Her sons live in the same city, but no one has come looking for her in the past three years, say attendants at the old-age home, run by Triveni Devi Charitable Society. “Since the death of my husband 10 years ago, I have developed some mental disorder and tend to forget eating or taking medicines on time,” says Devi, flipping through the photographs from her younger days, kept carefully by bedside. “My children would often speak harsh words for being a burden on the family.” She left home after one such tiff with her son’s family.

There is no dearth of such stories of loss and loneliness in the country, which is undergoing a rapid transformation—both socially and demographically.

There is no dearth of such stories of loss and loneliness in the country, which is undergoing a rapid transformation—both socially and demographically.

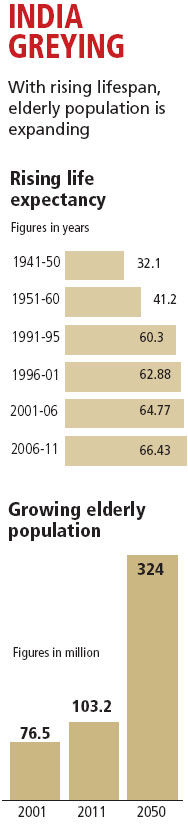

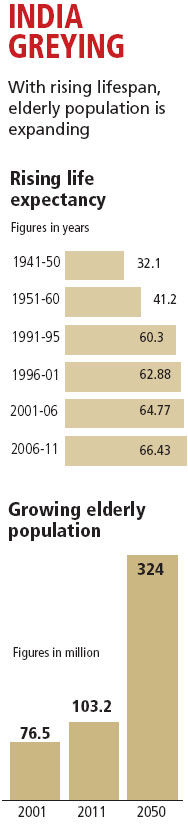

Due to improved healthcare worldwide, the average lifespan of an individual has increased in the last few decades. India is no exception. According to the Census of India, the life expectancy of an Indian was 52 in 1975. Today, an average Indian man lives beyond 67 years and women about 70 years, according to the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. There is, however, a downside to the success story. Increased longevity means there are more elderly people than before. From 56.5 million in 1991, the number of elderly (those above 60) has increased to 103.2 million in 2011—the largest ever in the country’s history. According to the Union Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), by 2050 a greying India will have a quarter of its population to look after. A sizeable portion of them would be very old (80 and above) and widows, as women tend to live longer. Most of this ailing, frail population would be living in villages (see ‘India greying’ and ‘State of our elders’).

Many other countries are witnessing similar demographic change. But the rapidly ageing population is a matter of worry for India because of two reasons. One, attitude towards the elderly is changing. Though India’s traditional piety requires children to look after their parents, nuclear families have little time or resources for their ailing parents. Increased migration from rural areas also forces the younger generation to leave their elders alone back home. Finances are stretched and healthcare expensive. Worse, nearly 90 per cent of the elderly worked in the informal sector and do not receive social security coverage, like pension and mediclaim, post retirement, according to HelpAge India. They either continue to work beyond retirement age or suffer from neglect and alienation.

Two, the government seems little bothered about the growing acuteness of the problem and ill-prepared for the mounting responsibility. Apathy of the political class is evident from the fact that the ruling United Progressive Alliance spent just 151 words for the elderly in its 81-page Report to the People 2012-13. There was no mention of the performance of the programmes for the elderly in the report. This is surprising because the average age of the Cabinet is 65 years. Even in this general election, the manifestos of major political parties pay mere lip service to the issues of the elderly.

Care, an age-old problem

What goes without saying is that older people have a depleting health that needs constant care and management. The problems could range from debilitating joint pain and constant coughing to life-threatening heart diseases and cancer. A 2011 report by the Ministry of Social Justice shows that 160 of every 1,000 elderly living in urban areas suffer from heart diseases. Urinary problems are more common among aged men, while most aged women suffer from joint problems. Of every 1,000 elderly, nearly 64 in rural and 55 in urban areas have one or the other form of disability, such as hearing difficulty, poor vision or locomotive impairment.

Lately, depression has emerged as another common ailment among the aged. According to a study published in Neurosciences in Rural Practice in 2011, about 22 per cent of the elderly in India—or every fifth elderly in the country—are depressed. The worldwide average is 10.3 per cent. The study, led by Ankur Barua of Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Malaysia, analysed figures from Asia, Europe, Australia, North America and South America. This is a scary situation because more often than not an elderly suffers from more than one disease.

“These are the problems of old-age and are interrelated. There is natural decay of the body and every ailment need not be treated the way it is done for other age groups,” says A B Dey, head of the geriatrics department at AIIMS. “So, there is a need for geriatricians who are trained to see the person in the context of age and give less medicine for maximum advantage.” Besides, Dey says, most elderly are not aware of their illnesses, even if they are at a later stage of life-threatening diseases like heart problems and cancer. They think the symptoms are part of the ageing process. Between July 2012 and July 2013, his department and the Indian Council of Medical Research assessed the health of 1,643 above-60 people who visited the general out-patient department of AIIMS and followed them up for one year. To their surprise, they found only 15 per cent patients alive by the end of the year; 30 per cent died within the first month of treatment. “We now check patients for a set of diseases even if they approach us for some other ailment,” he adds.

For someone like Urmila Devi, who suffers from high blood pressure, diabetes and neurological disorder, visiting a geriatrician would not only save her from the trouble of approaching multiple doctors and save precious pension money, she would also be diagnosed of any hidden disease before it is too late. But a geriatrician is not easy to come by.

For someone like Urmila Devi, who suffers from high blood pressure, diabetes and neurological disorder, visiting a geriatrician would not only save her from the trouble of approaching multiple doctors and save precious pension money, she would also be diagnosed of any hidden disease before it is too late. But a geriatrician is not easy to come by.

Heartless attempt

Much hope was pinned on the Union health ministry when it opened National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) in June 2010. It is the first programme with special focus on the health requirement of the aged. Under NPHCE, the ministry promised to establish geriatric departments in eight super-specialised hospitals and strengthening healthcare facilities for the elderly in each district. Under the first phase (2010-2012), NPHCE was planned to cover 100 districts of 21 states and union territories. The remaining 540 districts were to be covered during 2012-17. But it is yet to keep its word.

Lov Verma, secretary of the ministry, told Down To Earth, “We have opened geriatric out-patient departments in eight hospitals and indoor (hospitalisation) services in six. We plan to open National Institutes of Ageing (nodal agency for research and healthcare) at AIIMS and Madras Medical College in Chennai.”

Doctors at the geriatric departments say they are yet to receive the promised Rs 20 lakh per annum, meant for subsidising medicines and tests. District-level implementation of the programme also remains a far cry.

The government’s apathy towards the elderly becomes evident from the fact that in 2012-13, the ministry released only Rs 1.15 crore of the Rs 50 crore allocated for the elderly under National Health Mission. The same year, the ministry released Rs 68.56 crore out of the allocated Rs 150 crore for NPHCE. However, the utilisation of the fund remains poor. According to a January 2014 report by industry body ASSOCHAM and KPMG, a company that offers advisory services, Kerala, the state with one of the largest elderly populations, has utilised only 8 per cent of the Rs 8.79 crore received under NPHCE.

Such apathy comes as no surprise in a country that drafted its National Policy on Older Persons only in 1999. “The policy, meant to address issues relating to ageing in a comprehensive manner, failed to provide relief to the elderly, primarily due to lack of focus of the government and no will towards its implementation,” says Cherian.

Financial crunch, health problems and living alone have emerged as the top three fears of the elderly, according to the ASSOCHAM-KPMG report. And cashing in on these are the real estate sector and private healthcare facilities.

Home, old-age home

With attitude towards the elderly changing, the business of care booms

Vandana Das (name changed), 71, did not realise when her behaviour changed. She became rude and withdrawn, and could not manage her daily chores. Doctors diagnosed her of suffering from dementia. The son, a bank executive in Pune, bought a two-bedroom flat in a retirement colony and moved his mother there. She is now under the full-time care of a nurse.

The widening gap between the elderly and their children has opened new avenues for private players who have introduced concepts of elderly care at home to retirement homes.

People in their late 30s and 40s are encouraged to invest in retirement homes. According to a 2011 report by Jones Lang LaSalle India, a real estate consulting company, the current demand for retirement homes is 300,000 units. “Indian market has only 4,000-5,000 such units, catering to less than 2 per cent of the demand,” says Ankur Gupta. He is joint managing director of one such housing colony, Ashiana Utsav in Bhiwadi township in Rajasthan’s Alwar district.

A gated community with double security check for every visitor, Ashiana Utsav provides architecture, facilities and services for people above 55. It has 650 flats, of which 458 are occupied by old couples and singles. Corridors are equipped with soft-textured handrails to provide extra support to the very old people. Special care is being taken to ensure that electricity is available round-the-clock and lifts are always functional. “If you have not seen old age you really do not know what relaxation feels like,” reads a wall-hanging in the activity centre.

This was precisely what was in the mind of Subhash Chandra Tyagi while he was looking for a house to settle down after retiring from a government eye hospital in Modinagar, Uttar Pradesh, as medical superintendent. “Our balcony opens to the park where we spend hours sipping tea, reading and talking to all the passers-by,” says Subhash. “Companionship is the primary need in old age,” says Suman, his wife. “Understanding this aspect, the colony developers have connected all flats with free intercom.”

The staff of 10 organises different activities for the residents, rekindling their long-dead hobbies and interests. Subhash has taken to playing guitar, a hobby that had once made him apple of everyone’s eye in his medical college. “We also organise cultural and religious activities, talks on health-related topics, outings and a monthly get-together to celebrate all birthdays and marriage anniversaries of that month,” says Devdeep, activities manager.

Tyagi bought the three-bedroom flat for Rs 12 lakh in 2004. Today, its cost is Rs 30 lakh. In addition, he pays Rs 2,500 as maintenance charge every month. This is an expensive proposition for most elderly people, who are poor or belong to lower-middle class section. For them, there are just 700-odd old-age homes across the country. According to Delhi non-profit Dada-Dadi, 325 of them are managed by charitable societies with the help of government and provide free-of-cost stay facilities. The rest are managed by private players. But getting a bed in an old-age home is as arduous an exercise as surviving the old age.

“Old-age homes and retirement homes should be treated as shelters, not long-term care homes,” says Dey. “Such arrangements are good for people till they are 75 years old. After that they need continued care and management.” Neither retirement homes nor old-age homes have such arrangements and the residents are visited by a general physician once or twice a week. The closest tertiary hospital to Ashiana Utsav is in Manesar, a 40-minute drive from Bhiwadi.

Home care solutions

Home care solutions are also emerging as a response to the need of the elderly. Epoch Elder Care is one such company in Gurgaon, Haryana. “Our Elder Care Specialists (ECS) offer intellectual companionship to the elderly at their homes,” says Tanvi Dalal, head of human resources at Epoch Elder Care. They accompany the elderly on outings, read and discuss articles with them, play games, help them go back to their hobbies and discover new ones, assist with email, Facebook and Skype, help them blog about their topics of interest and share stories. We also provide them health management and check-ups for blood pressure and blood sugar. For patients of dementia and Alzheimer’s, full-time trained attendants are available,” says Dalal. There is a high demand for attendants for the elderly and it is a great career potential, she adds. Depending on the length and number of sessions and services, hiring an ECS can cost between Rs 12,000 and Rs 14,000 a month.

A similar model, but relatively low-cost, is being tried by a Bhubaneshwar-based non-profit, Sushruta. It provides nurses at just Rs 5,000 a month. “Most of our nurses are women and from rural Odisha. We train them in elderly care,” says Rashmi Pandian, head of Sushruta. “Their stay and food is managed by the family they serve. We ensure that they get proper bed and clean bathroom and toilet, and are treated with dignity.”

But there is no conclusive evidence to prove that home-based care helps increase the lifespan of an elderly, according to a study published in Plos One in March 2014. Researchers from University College London (UCL) and the University of Oxford said this after reviewing 64 studies done in the past 20 years on elders who received home care visits. Perhaps, nothing can replace the want to be with one’s own family.

Making use of the wisdom

To reduce generation gap between children, youth and the elderly, Ayaad Foundation, a not-for-profit company, has launched an innovative model in Kumbhalgarh in Rajasthan. It is building a residential complex in the tourist town. The elderly can book a residence for themselves. But unlike retirement homes, they will not own the property. They can stay there as long as they live, with the foundation taking care of their food and other day-to-day needs.

“There are two designs. One-bedroom cottages that can accommodate two-three people comes for Rs 12 lakh. Single rooms, meant for two persons, costs Rs 8 lakh,” says Nidhi Agarwal, founding member of Ayaad. The foundation plans to set up a facility for children with special abilities in the complex so that the elderly residents can keep themselves engaged by looking after them. “We also plan to bring children of migrant labourers and unemployed youth to the campus. The residents can assist them with education, work and skills. This way they use their knowledge and time and help society grow,” says Agarwal. The project is expected to be started by the end of the year.

How effective are models of care?

There is a growing interest for such models among a certain section of society. But analysts warn against them. “Till date there is no model catering to the complete range of old age needs like healthcare and productive ageing,” says Cherian. “The concept of retirement community is driven primarily by real estate developers, who lack skills and credibility in integrated living and lack understanding of age-specific care needs.”

But in the absence of a system to meet healthcare needs, like subsidised medicines, the elderly have nowhere to turn to (see box). In many cases, the meagre old-age pension received by a BPL elderly as a social welfare measure goes into buying medicines. Consider this. Every month Roshan Sahni, 78, a resident of Kalkaji area in Delhi, anxiously waits for per pension of Rs 1,000, which he receives under Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme. “I am on medication for diabetes and hypertension for seven years. Last year, I was diagnosed with first stage lung cancer. I have been put on medicines for that too.” Sahni is lucky to be living with his son.

In the absence of a functioning national programme, a couple of municipal corporations have tried to intervene at their levels to provide healthcare to senior citizens. In 2003, Indore Municipal Corporation and in 2007, Gwalior Municipal Corporation initiated health insurance schemes for the elderly from poor financial backgrounds. It provided insurance cover of up to Rs 20,000 for hospitalisation expenses. But care for critical illnesses and medicines, that form a bulk of the medical expenses, are not part of the scheme. The ASSOCHAM-KPMG report says the scheme did not take off.

Being wise

Several poor countries are providing good healthcare to their elderly. All India needs is a strong political will

In the first overview of wellbeing of older people around the world, HelpAge International and the United Nations Fund for Population Development have prepared an index. On the Global AgeWatch Index (GAWI), released in October 2013, India ranks a lowly 73rd among the 91 countries. This when countries like Bolivia, Chile and Sri Lanka, which have high poverty level, rank much above India.

“India’s dismal performance shows that despite catering to a large elderly population, we do not have mechanisms in place to ensure them healthy ageing with other social security measures,” says Cherian.

International experience shows a combination of welfare policies lead to healthy and quality life for the elderly. Even in the absence of a well-endowed economy, strong political will can do the job.

Take Bolivia for instance. Despite being one of the poorest countries, it ranks 46th on GAWI. Analysts link its achievement to the government’s progressive policy for the elderly. In 2009, the Bolivian government rewrote the Constitution to include the rights of elderly, who account for 10.4 per cent of the country’s population. Its National Plan on Ageing ensures free healthcare to the elderly. Unlike India, which has a pension scheme for elderly below the poverty level, Bolivia’s pension scheme serves all those above 60. Called Renta Dignidad, literally dignity of the elderly, the pension scheme offers US $340 a year to those who do not receive a retirement pension, and US $255 to those who do. At the core of Rental Dignidad is the policy of income redistribution. It is financed by levying direct taxes on oil and gas and by using the dividends of public companies. Salaried citizens, including military personnel and apprentices, also contribute 10 per cent of their income towards it. In addition, 20 per cent of the contribution by the salaried goes towards pension for the disabled elderly. They receive an increased amount of pension from the age of 50 depending on their degree of disability. For example, if an elderly person’s degree of disability is 50, the pension amount would be 50 times his average earnings in the last five years. Disability pension ceases at the age of 65 and the person becomes entitled for regular pension.

| REALITY CHECK

Empty promises of Indian government

1992: Government launches Integrated Programme for Older Persons to ensure basic amenities like shelter, food, medical care as well as entertainment opportunities. Under the programme, NGOs set up old-age homes with 90% Central aid. An additional Rs 6,77,000 per year is given to run the homes

So far only 352 old-age homes have been established

1999: National Policy on Older Persons (NPOP) is drafted. It is revised twice, first in 2008 and then in 2010, keeping in view the changing demographics and socio-economic patterns

The policy is being assessed by state governments

2007: Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizen Act comes into force. It penalises for abandoning senior citizens, provides for establishment of old-age homes, ensures protection of life and property of the elderly

Elders find it difficult to pursue the tedious judiciary process

2010: The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launches the National Programme for the Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE). Provisions of NPHCE are similar to those of NPOP. The only difference is it was launched by a different ministry. There is no difference in implementation.

Implementation is almost nil; funds are yet to be utilised

Options for the elderly are few, far-fetched

- Old-age homes: very few with no long-term care

- Retirement home: Costs upwards of Rs 12 lakh; most elderly are poor or marginal and cannot afford it

- Pension scheme: 10% receive pension as retirement benefit. Only BPL elders are eligible for government pension of Rs 200-Rs 1,000 a month

- Health insurance: A few private and nationalised insurance companies offer health cover for the old. It comes at a high premium of at least Rs 5,000 a year. The premium rate increases with the onset of every chronic illness, which is common in old age

- Reverse mortgage: One can earn every month by mortgaging property to a bank or financial institution. In 2013, the income was declared tax- free

|

“Renta Dignidad is part of a strategic set of programmes that direct resources towards measures that secure and ensure a life of dignity for Bolivians,” wrote Marcelo Ticona Gonzales, in Social Protection Floor Experiences, a 2011 publication by the International Labour Organization. As director general of pensions at Bolivia’s public finance ministry, Gonzales is responsible for implementation of the scheme.

Chile, Bolivia’s immediate neighbour, also ensures quality of life to its elderly. GAWI ranked it at 19th, saying “older people have fared as well as the overall population”. This remarkable achievement has been made possible by a state-sponsored insurance scheme, Acceso Universal de Garantías Explícitas (AUGE), which offers financial protection for 66 medical conditions, including elderly-specific health needs, such as degenerative osteoarthritis and tooth loss. People without any direct income, most of whom are the elderly, are exempt from paying premium for the insurance scheme. Resources for AUGE are drawn from consumer tax, tobacco tax, customs revenues and sale of the state’s minority shares in public health enterprises.

Under AUGE, healthcare can be availed in private as well as public healthcare facilities. Unlike India, Chileans prefer government hospitals over private health centres. In the 1990s, the Patricio Aylwin-led government, which brought in a democratic system after 17 years of military rule, set up an impressive infrastructure that provides high quality healthcare by spending a whopping US $86.5 million a year. Under the military rule US $15 million a year was spent on healthcare. The investment is now paying off.

Government data shows that 74 per cent of the beneficiaries belong to the poorest section. Though AUGE caters to the entire population, it helps the elderly as they form an important part of the vulnerable section with no direct means of income.

India’s neighbour Sri Lanka also ranks 45th on GAWI. This has been made possible by long-term investments in education and healthcare facilities for the entire population.

Can India learn from others’ models?

“We can, but it is not advisable to copy,” says Dey, head of the geriatrics department at AIIMS. “There is no ready-made solution for care of the elderly. I started working in the field to find solutions. By the time I was in the committee and we were finalising NPHCE, I realised there is no model that fits our country. Ageing population is a new phenomenon for India. The society will evolve itself to find solutions,” he says, adding that the focus should be on long-term care. “It’s not just about house and shelter, but management of chronic diseases and deteriorating motor skills.”

| How to age gracefully

Ageing is an ambiguous term. Though the Indian government has declared those above 60 as elderly, no one is sure about the cut-off age and it varies from society to society. Scientists worldwide have long been trying to understand the ageing process. One such initiative is Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Ageing (BLSA) by the National Institute of Ageing of the US Department of Health and Human Services. Started in 1958, the study enrolled 3,000-odd volunteers, who were in their 20s, from across the world and followed them up to generate data about ageing. Every year, BLSA conducts a three-day check-up on the volunteers to collect data. Some facts about ageing—for example, light physical exercise keeps a person healthy in old age—are the result of its research. The research has thrown up a few other interesting information. Its July 2010 report shows that obesity is not as unhealthy as thinning for the elderly. Mortality rate was higher among thin adults (with body mass index of 19) than those who were obese. The study has found that signs within the body emerge as much as 20 years before symptoms show up. Those who experience an accelerated decline in memory, verbal intelligence and executive function earlier in age, are more likely to develop dementia later. Importantly, the study has opened up possibilities of defining ageing differently, as individuals experience. Perhaps this is the reason Mark Twain once said: “Age is an issue of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.” |

Several other healthcare experts also emphasise on long-term care for the elderly. “The maximum burden on the healthcare system is caused when a patient comes with acute trauma,” says Santosh Rath of George Institute of global Health, University of Oxford. “If long-term care, with early detection and quick treatment can be given to patients, such cases will reduce. This will benefit the healthcare system and the economy.” For accidental illnesses, such as hip fractures, which are common across the world, the elderly need to be treated within 36 hours. “So we need to bridge the gap between good practice and actual practice,” says Rath. George Institute has initiated a study on hip fractures in India.

Early this year, HelpAge India prepared a set of healthcare measures and submitted them to political parties to be included in their manifestoes. As expected, very few of these measures find a mention in the manifestos.

One demand is extending geriatric care to all districts and implementation of Rajiv Arogyasri Scheme, a community health insurance scheme that provides financial protection of up to Rs 2 lakh a year to BPL families. It covers serious ailments requiring hospitalisation and surgery. Some states have adopted the scheme, but only Andhra Pradesh is implementing it. The state has gone an extra mile by introducing Elder Helpline under the scheme so that care is just a phone call away.

The other demands of HelpAge India include setting up at least one old-age home in each district, extending government-sponsored health insurance schemes from BPL to all the elderly, providing pension of at least Rs 2,000 per month to all elders, except those who pay income tax. “If provided as a package, these measures can address the critical needs of the elderly in the country,” says Cherian. Some of the schemes exist on paper, but it’s time the government implemented them.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

There is no dearth of such stories of loss and loneliness in the country, which is undergoing a rapid transformation—both socially and demographically.

There is no dearth of such stories of loss and loneliness in the country, which is undergoing a rapid transformation—both socially and demographically.

For someone like Urmila Devi, who suffers from high blood pressure, diabetes and neurological disorder, visiting a geriatrician would not only save her from the trouble of approaching multiple doctors and save precious pension money, she would also be diagnosed of any hidden disease before it is too late. But a geriatrician is not easy to come by.

For someone like Urmila Devi, who suffers from high blood pressure, diabetes and neurological disorder, visiting a geriatrician would not only save her from the trouble of approaching multiple doctors and save precious pension money, she would also be diagnosed of any hidden disease before it is too late. But a geriatrician is not easy to come by.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.