Despite 40 years of efforts and huge resource allocation, drought continues to hit the same districts over and again

Chaos and conflicts similar to those in Marathwada are brewing across the country, which faced an extremely dry southwest monsoon and even drier winter monsoon. In November 2018, the Jharkhand government declared 18 of its 24 districts drought affected. In Koderma district, which received 55 per cent less rainfall than what it usually receives, farmer Ashok Turi of Dhargaon village says his savings are drying faster than the waterbodies around the village.

After his kharif crops failed due to deficit rainfall last year, Turi had invested in sowing rabi crops on his 2.5 hectare (ha) farmland this winter. But they too have failed to germinate.

“I may soon have to work as a daily wage labourer to sustain my family,” says the 50-year-old. Condition is no different for Deep Narayan Yadav. He took the risk of hiring water lifting motor pumps at the rate of Rs 200 per hour and sowed wheat in one-third of the 1.2 ha farm. But he could not arrange sufficient water and his entire field has turned brown. In north interior Karnataka, which falls in rain shadow area, Subanna Biradar says the loss in productivity has been over 50 per cent despite using borewells. He grows sugarcane on his 1.2 ha farm with the help of a single borewell. The situation is no better in Bihar, West Bengal, Goa, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Meghalaya, Karnataka and Arunachal Pradesh where more than 50 per cent of the districts received deficit rainfall.

Surprisingly, drought is not new to India. On an average, every third year gets a drought in these areas. Rainfall data over the past century indicates that there has been a severe drought every eight to nine years. The government’s concentrated efforts to make the country drought-free also date back to the 1970s. So far, it has introduced 10 national programmes, and invested some R3,97,011 crore since the 1990s to drought-proof the country (see ‘How funds fail’). “Over the past 20 years, the government has not only increased money allocated to drought-mitigation measures, but is also employing sophisticated tools like the geographic information system (GIS) for preparing action plans keeping climate change in mind,” says Biksham Gujja, chairperson, AgSri Agricultural Services Pvt Ltd in Hyderabad that works on livelihood development and food security.

Yet, a 2018 research paper, jointly published by the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)-Indore and IIT-Guwahati says at least 133 of the 634 districts in the country face drought almost every year; most of them are in Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Chhattisgarh. In southern India, Tamil Nadu was the best performer, with 56.74 per cent drought-resilient area. It was followed by Andhra Pradesh (53.43 per cent) and Telangana (48.61 per cent), while Karnataka (17.38 per cent) and Kerala (19.13 per cent) were at the bottom of the list. Among the northeastern states, Assam at 20.72 per cent had the lowest percentage of resilient area.

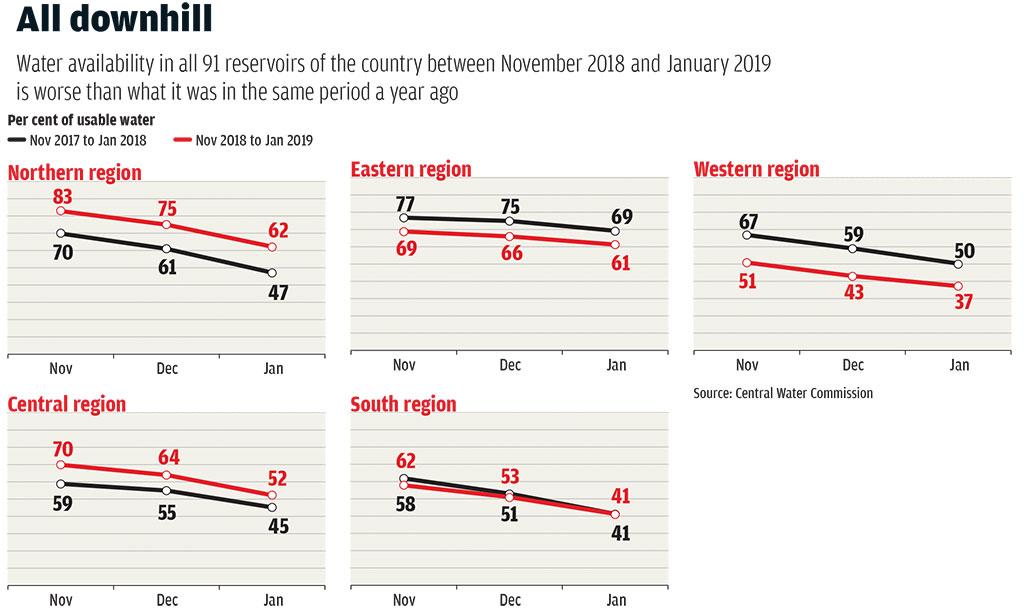

An analysis of usable water storage capacities in all 91 reservoirs in India shows most now hold less water during the dry months of November-January (see ‘All downhill’).

Where does the problem lie?

Gujja says it is difficult to answer whether the water conservation structures constructed under various programmes are efficient enough to tackle drought. The problem lies in the fact that watershed programmes in the country are being implemented like any other government programmes. “We try to assess their efficacy by measuring bunding, silting and area covered, whereas its effectiveness depends on its impact on crop production and how it benefits the farmers,” says Gujja.

Consider Karnataka, one of the least resilient states identified by the 2018 research paper. An assessment of the list of drought-prone areas between 2011-12 and 2018-19, shows 16 of the state’s 30 districts get affected by drought over and again. Between 2015 and 2018, shows the website of MGNREGS of Karnataka, over 78,000 water conservation and harvesting structures have been built. More than 27,000 ponds were renovated under this scheme since 2015-16. Belagavi district’s water conservation project earned Union Ministry of Panchayati Raj’s award for the best effective MGNREGA implementation in the state for 2016. But the district continued to be drought affected even post-2016.

GS Srinivasa Reddy, director, Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre, says the capacity of the farmers in adapting water conservation technologies is woefully low and this causes a repeat of droughts in the same districts. Ravindra Chary, acting director, Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad, suggests long-term crop-, watershed- and water management-based solutions for drought mitigation. If water is not available, one has to plan the cropping pattern in the area intelligently.

Gujja says there is a need to understand that watershed program mes are not meant for irrigation. Water use has to be restricted where such projects are being implemented so that the improved soil moisture gets used. Communities that use water optimally and raise crops that are less water-intensive should be incentivised, he says, adding that ponds for storing water should be encouraged but planning should be based on traditional knowledge.

(With inputs from Chhandosree and Shreeshan Venkatesh)

(This story was first published in Down To Earth's 1-15 March 2019 print edition)

(This article is the fourth in a series of stories that will track the drought situation in India)

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.