Sixteen years after India banned the veterinary use of diclofenac to save its vultures, three other drugs revive the old challenge

On March 14, the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), India’s oldest biodiversity conservation group, wrote a letter urging the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) to ban the use of three veterinary drugs known to kill vultures in the country.

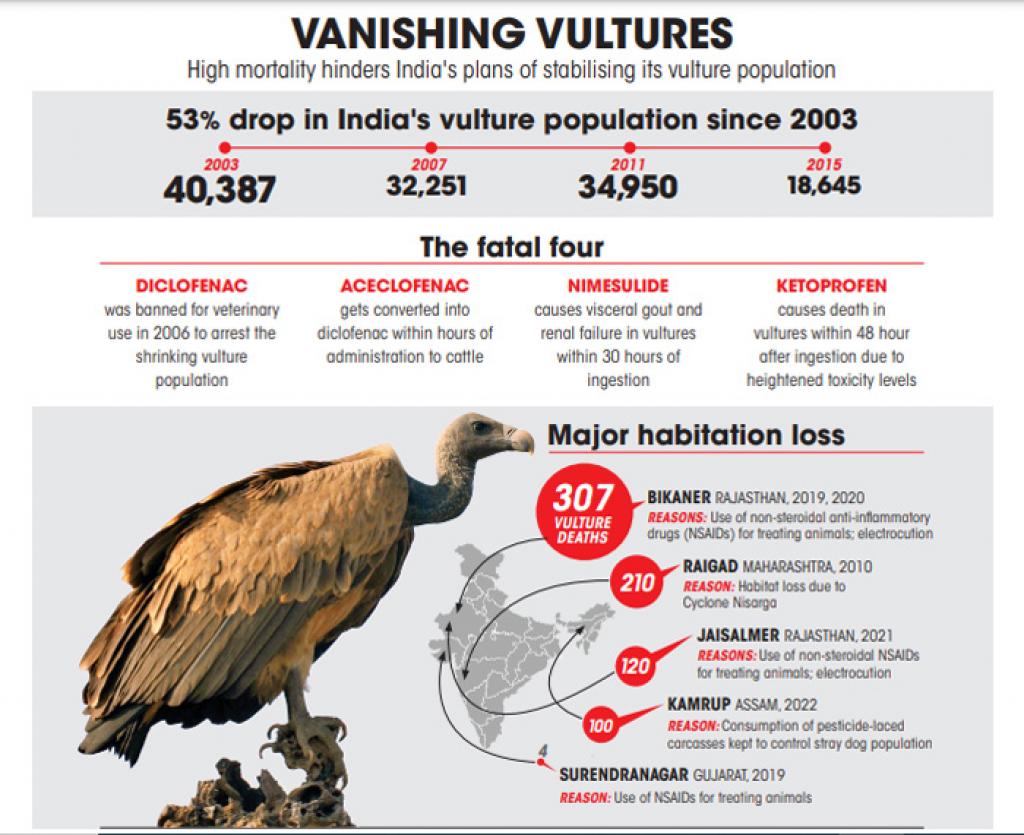

The letter warns that the rampant use of the three non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) threatens to undo the Centre’s two decades of work to arrest the dwindling vulture population in the wild. Surprisingly, the three drugs—aeclofenac, ketoprofen and nimesulide—were introduced as alternatives to diclofenac, the NSAID that India banned in 2006 for animal use because it caused widespread vulture deaths.

“Deaths caused by NSAIDS are invisible. Birds die two-three days after ingesting the medicine, making it difficult to establish a clear link,” says Chris Bowden, co-chair, Vulture Specialist Group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature. He says India has slowed down vulture mortality rate, but not stabilised the population.

Vultures were quite common till the 1980s. Currently, eight species in the country face extinction, says Rinkita Gurav, manager, raptor conservation, World Wide Fund for Nature, India. The country’s vulture population crashed from over 40,000 in 2003 to 18,645 in 2015, as per the last vulture census conducted by intergovernmental body Bird Life International.

Even diclofenac, which is only permitted for human use, is being misused for cattle treatments. “Such treatments are usually prescribed by quacks,” says Vibhu Prakash, deputy director, Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS).

Default choice

“You do not need a prescription to get your hands on diclofenac or any other NSAIDS here,” says Dau Lal Bohra, wildlife researcher and head of department, zoology, Seth Gyaniram Bansidhar Podar College in Rajashtan’s Jhunjhunu district.

In 2005-06, a little over 10 per cent of cattle carcasses had diclofenac residue. This came down to below 2 per cent by 2013, except for Rajasthan where it was still over five per cent, claims India’s second National Vulture Conservation Action Plan (2020-25), released by MoEF&CC. Vulture populations are considered safe if the diclofenac prevalence in carcasses drops to below 1 per cent.

Bohra estimates Bikaner, home to the Jorbeer vulture conservation centre and animal carcass dumping site, has a vulture population of 1,795 (give or take 137). In the absence of a national death registry, Bohra has kept a log of vulture deaths in the district for research. He has counted 184 vulture deaths in the district in 2020, which is roughly 10 per cent of the total vulture population in the district.

“In the majority of cases, the postmortem report shows the deposition of white precipitate on the kidneys and heart of vultures, indicating death by NSAIDS,” he says. Almost 30 cattle carcasses are dumped at the Jorbeer reserve daily.

“Even if one of them has traces of NSAIDS, it will be consumed by 45-50 vultures,” he says. Radheshyam Bishnoi, a conservationist in Jaisalmer, says the district saw 120 vulture deaths last year. In some years, the number goes up to 300. “At least 20 vultures have died this year. Some of them have died due to electrocution, while some others have died due to the consumption of NSAIDS,” he says.

When Down To Earth visited Rajasthan’s second-largest cattle shelter in Bhadriya village, Jaisalmer, it found that diclofenac and other NSAIDS are part of its treatment process for cattle. “They are effective against seasonal flu. We also use them as painkillers. There are 20-30 cows that undergo treatment at a point of time,” says a compounder at the cowshed, which has over 50,000 heads of rescued cattle. The cowshed dumps almost five carcasses a day.

Pesticide poisoning also threatens vultures across the country. On March 17, 2022, Kamrup district in Assam reported 97 vulture deaths after they consumed two pesticide-smeared carcasses that had been kept by farmers to kill stray dogs.

Empty promises

India’s vulture conservation action plan for 2020-25 recommends a ban on the veterinary use of the three drugs. It adds that the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) must institute a system that removes a drug from veterinary use if it is found to be toxic to vultures.

The country is also a signatory to the Convention on Migratory Species’ Multi-species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures, which recognises NSAIDS as a major threat to vultures in India. Still, little seems to have moved on the ground.

“The drugs have been deemed to be safe for livestock by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation. We have reached out to DCGI (which heads the department) to ban them. They have a technical committee to make such decisions, but the process is lengthy,” says Prakash.

He adds that BNHS has written to the chairpersons of the vulture breeding and conservation centres in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana to garner support to ban the drugs in the states. “We have also reached out to the Wildlife Department,” he says.

Small victories

Till recently, train collision was a major reason for vulture deaths in Jaisalamer and Bikaner. It was arrested in 2019 by the construction of walls along the railway tracks. “Stray cows would often forage near the railway tracks and get hit by trains. Then vultures would come to eat the carcasses and get run over by trains,” says Bishnoi. In January 2018, Jaisalmer saw 42 vulture deaths because of train collision.

In 2015, Tamil Nadu became the first state to ban the veterinary use of ketoprofen in Nilgiri, Erode and Coimbatore districts. “The government wants us to produce more scientific evidence to put a state-wide ban,” says Subbaiah Bharathidasan, cofounder of non-profit Arulagam.

He says the impact of the ban will be felt in the long-run as vultures are slow breeders who lay only one egg a year, which has a survival rate of about 60 per cent.

Sources: Bird Life International and media reports

In 2020, Goa’s Directorate of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services urged the Food and Drugs Administration Department to consider a ban on ketoprofane and aceclofenac for treatment of animals.

There are also safe drug alternatives available to treat cattle. The vulture action plan recommends meloxicam over diclofenac. Prakash says tolfenamic acid is the other safe option.

The challenge, though, is a lack of awareness. Bohra says he conducted a study in 2014-15 in Bikaner and found 7,500 vials of NSAIDS were being used for cattle treatment every month. “The district, like most others in the country, has limited trained veterinarians and a high number of quack doctors who prescribe drug overdoses,” he says.

He says cowsheds should maintain medical records and note down the time of death of their animals. The treatment should decide whether the body is to be cremated or sent to a dumping ground.

This article was first published in the 1-15 April, 2022 edition of Down To Earth

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.