Though bamboo can now be legally harvested, local communities are protesting as they face administrative hurdles

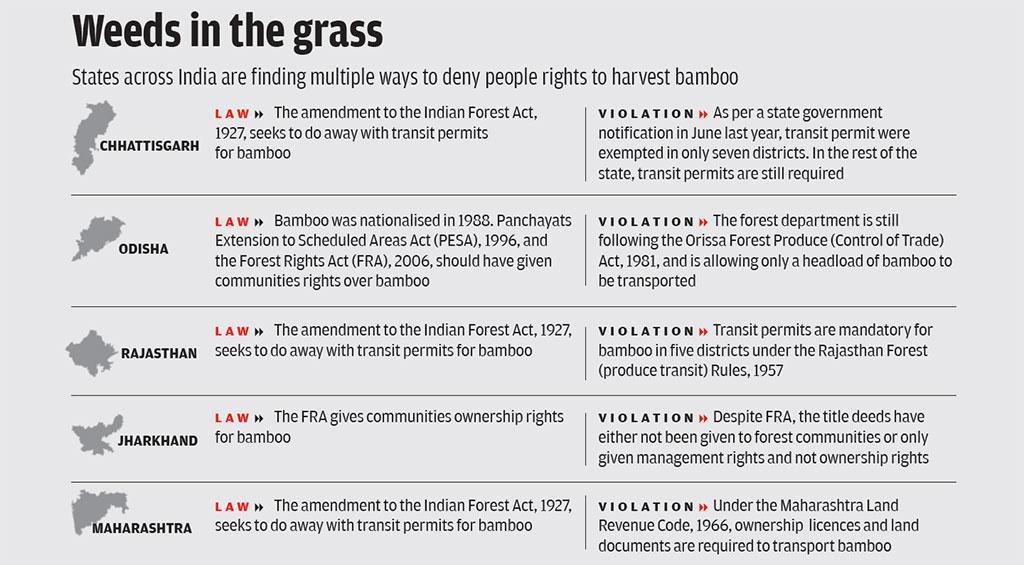

When the Union government amended the Indian Forest Act, 1927, in November last year by categorising bamboo as a grass, and not as a tree, there was great jubilation. It was believed that the amendment would enable poor communities to legally harvest and trade bamboo. But local people across India are now facing a number of administrative problems to harvest bamboo and earn a livelihood. For instance, in Udaipur district, Rajasthan, 16 villages, launched a bamboo satyagraha on February 21 after the local administration refused to give permission to cut bamboo.

“We sent letters to the collector and the block development officers, among others, but did not get any response,” says Devilal Doongri, a resident from Amiwara. The village has around 30,000 bamboo culms which can fetch around Rs 2 lakh. “Harvesting will not only bring money for village development, but also prevent bamboo intrusion into our fields,” says Ganga Ram Dangi of Matata village in Badgaon block. Though Amiwara finally got permission, the other 15 villages are awaiting approval.

The historic amendment says: “The farmers are facing hardships in getting the permits for felling and transit of bamboos within the State and also for outside the State, which has been identified as major impediment of the cultivation of bamboos by farmers on their land… Hence, it was decided to amend… the said Act so as to omit the word “bamboos” from the definition of tree, in order to exempt bamboos grown on non-forest area from the requirement of permit for felling or transit.” But on the ground, it is a different story.

“The Rajasthan Forest (produce transit) Rules, 1957, make the requirement of transit permits mandatory,” says O P Sharma, the district forest officer of Udaipur. Sharma adds that the reason for this requirement is because bamboo grows naturally and there is a probability of stealing from forestland. Sharma admits the rules are a hurdle in realising the intention of the amendment to promote trade in bamboo.

Odisha is facing other kinds of problems. In January this year, village communities in Pipadi and Jamguda in Kalahandi district were denied access to take bamboo out of the forest area. They were told that they could transport bamboo outside the forest, only if it was done manually or by using a cycle, thereby making a mockery of their right over minor forest produce (MFP). In February, more than 100 Gram Sabhas in the state gave an ultimatum to the forest department that they will exercise their rights under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, and issue transit passes on their own.

States too need to amend laws

Experts say that overlapping legislations have added confusion to people’s rights over bamboo. Priyanka Singh, chief executive, Seva Mandir, a Udaipur-based non-profit that has been helping villages in the district with their common resources, says that though there are legal instruments that give forest rights to people like the Panchayats Extension to Scheduled Areas Act (PESA), 1996, these laws aren’t clear. “For the last two years, the village residents were denied their rights over their produce. It was a huge opportunity cost. If the permissions were given when it was asked, the next crop would have been ready by now,” she says.

“Under the FRA, communities were given rights over bamboo as it is a MFP. PESA too gives them this right. Now the amendment to the Indian Forest Act, 1927, has cleared all doubts. Yet there are instances of rights being curtailed due to red tape,” says Barna Baibhaba Panda, a senior programme manager with the Foundation for Ecological Security, a Gujarat-based non-profit working in the field of conservation through collective action of local communities.

“The amendment in the section 2 clause 7 of the Indian Forest Act will not solve the issues related to bamboo. States have their own rules and they’ll continue to follow them. The government needs to amend Section 41 and 42 of this Act, which gives state governments the power to frame their own laws,” says Suneel Pandey, a former Indian Forest Service officer.

Others say there is a need for some regulatory mechanism to enable harvesting and trade in bamboo. “Since bamboo is a commercially important commodity, there should be some regulatory mechanism. It need not be in the form of a forest department inspector. Instead, officials from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs or the Ministry of Panchayati Raj can play a leading role to evolve such a mechanism,” says Kanchi Kohli of Kalpavriksh, a non-profit. While the legality of harvesting and trade in bamboo is clear, the fruits of this well-meaning amendment remain unreachable.

(This article was first published in the 16-31st March issue of Down To Earth under the headline 'Barriers to harvest bamboo').

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.