Two recent raids have proved to be a setback for the lucrative wildlife trade in India. Though enforcement agencies are becoming more efficient, there are many rough edges to be ironed out

TWO HOARDS of banned animal skins and bones, worth about Rs 3.5 crore in the international market, were seized in Delhi on August 30 and September 1. The seizures exemplify the intelligence-gathering skills acquired by the Indian arm of the Trade Record Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce (TRAFFIC), the wing of the World Wide Fund for Nature that monitors trade in wildlife.

TWO HOARDS of banned animal skins and bones, worth about Rs 3.5 crore in the international market, were seized in Delhi on August 30 and September 1. The seizures exemplify the intelligence-gathering skills acquired by the Indian arm of the Trade Record Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce (TRAFFIC), the wing of the World Wide Fund for Nature that monitors trade in wildlife.

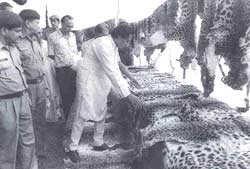

After four months of painstaking work, TRAFFIC-India investigators received information on the location of a large consignment of animal skins and bones that was to be shipped abroad. This resulted in a raid in the north Delhi settlement of Majnu-Ka-Tila, whose residents are mainly Tibetan refugees. The officials recovered 287 kg of tiger bones, 8 tiger skins, 43 leopard skins and more than 100 skins of other endangered animals, including foxes, snakes and crocodiles.

The authorities feel the major portion of the haul is from north Indian sanctuaries and the jungles of the lower Himalaya. According to TRAFFIC-India, wildlife poachers are particularly active in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and the jungles of the north-east.

Officials say poaching of the Indian tiger has risen because of the increasing demand from south-east Asian countries and China, where pharmaceutical factories consume the bones of 100 tigers each year. Kumar says such demand has "decimated the tiger population in China and brought the Russian tiger to the brink of extinction". As a result, in recent years much of the demand has been met by poachers in India.

Smuggling of tigers bones and skins is a lucrative business. One kg of tiger bones fetches $90 in India and eventually earns $300 in the international market. Other animal parts are equally, if not more, lucrative. The horn of the Indian rhino, coveted as an aphrodisiac, easily fetches $3,500-4,000 in Bahrain or Singapore. Kumar points out bones and skins are smuggled from India to several countries, from Saudi Arabia to Hong Kong.

Though the success of the recent raids are encouraging, enforcement and control agencies blame the lack of staff for the rise in poaching and add that they are also ill-equipped. Says Kumar, "Apart from TRAFFIC-India, which started functioning only in January 1992, there is no intelligence-gathering network to monitor wildlife trade in the country. Data on poaching is not collected, analysed and surveyed. As a result, although authorities are aware of wildlife trade being regularly routed through Calcutta, Patna, Kanpur, Madras and Bombay, they rarely have definitive information about the important link between the village level poacher and the retailer."

Kumar also draws attention to the lengthy legal processes involved in the enforcement of the Wildlife Protection Act. Since 1991, not one person has been convicted for a wildlife offence. Chand, for instance, was first booked in September 1974 and sentenced to jail in 1981. But he did not serve it because he was granted bail by a higher court. "Even judges do not take wildlife conservation seriously," says Kumar.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.