The co-benefits are clear, despite uncertainty on the sector’s emissions

Agriculture is a critical economic sector, especially in developing countries. It employs around 28 per cent of the global workforce in 2019, and around 43 per cent of the workforce in India. It contributes to climate change in multiple ways. Key sources of greenhouse gas emissions are:

Estimating global emissions from these sources, particularly from soil carbon loss, is tough. The natural systems involved are extremely complex, with multiple layers of feedback, and significant variations across regions and ecosystems. Nevertheless, a lot of technical progress has been made on this front.

Greenhouse emissions from agriculture are estimated at around 5.4 gigatonnes of carbon-dioxide-equivalent in 2017, around 10 per cent of the 53.5 gigatonnes of total emissions in that year. The top 10 historical emitters are China, India, the Soviet Union, Brazil, the United States, Australia, Indonesia, Pakistan, Argentina and the Russian Federation.

Source: FAOSTAT 2019

In addition to the technical challenges, there are also challenges with categorisation. Are emissions from fertilisers, for example, part of the agricultural or industrial sector? Biofuels similarly bestride agriculture and transport.

Can emissions from storing and transporting agricultural produce be usefully attributed to farmers (especially small farmers)? What about food waste, which the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) estimated as the third largest emitting ‘country’ in the world? These blurred lines result in estimates such as those below, which peg emissions from ‘food systems’ at 19 to 29 per cent of the global total.

Source: CCAFS CGIAR

Apart from emissions from agricultural activities, agriculture affects the process of carbon sequestration, by which greenhouse gases (GHGs) from the atmosphere are converted into biomass or trapped in the soil. Land is hence generally considered a ‘sink’, effectively the opposite of a ‘source’ of GHG emissions.

Forests generally sequester significantly more than crops or pasture. Do we account for forest land converted to the latter uses as ‘emissions’? What of innovations such as agroforestry?

The difficulties in isolating agriculture from other land uses, and isolating human-caused versus natural fluxes in the land sink, resulted in the creation of the ‘Agriculture, Forestry and Land Use’ (AFOLU) category.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s 5th Assessment Report of 2014 estimated that AFOLU (previously defined as Land use, Land Use Change and Forestry’ or LULUCF) accounted for approximately 20-25 per cent of total emissions in the year 2010. In 2019, it estimated AFOLU emissions between 2007 and 2016 at 12 GtCO2e each year, 23 per cent of total emissions in that time.

Source: IPCC AR5 (2014)

Domestic attempts to quantify India’s AFOLU emissions are underway, particularly in the form of a civil society-led GHG Platform coalition. Estimates of the sector’s contribution to India’s total GHG emissions have changed with successive phases of estimation.

An estimate in 2017 put 2013 AFOLU emissions at around 172 million tCO2e, and AFOLU’s contribution to total national emissions at 16 per cent. A 2019 estimate by the same authors revised the 2013 figures upward to approximately 292 million tCO2e, and the contribution of AFOLU to national emissions downward to 10 per cent. The picture is further complicated by the FAO’s estimate of India’s emissions from agriculture (not AFOLU) at 628 million tCO2e in the year 2013.

The challenge is to design climate-oriented policy in this sector in the face of deep uncertainty. Clues can be found in the IPCC’s recent Special Report on Climate Change and Land. First, the IPCC points to the fact that despite an approximately 33 per cent increase in per capita calories consumed since 1961, 820 million people are still malnourished.

Source: IPCC 2019

Policy to resolve inequitable consumption will focus on eliminating food waste — which the IPCC estimates at 25 to 30 per cent of food produced — and diversifying diets, which the IPCC identifies can mitigate between 0.7 and 8.0 GtCO2e per year by 2050. This will require increasing access to coarse grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and equitably reducing the carbon footprint of the meat industry.

The second unsustainable trend is the ever-increasing use of agricultural inputs (such as fertilisers) with diminishing increases in yield. The IPCC considers that 2.3 to 9.6 GtCO2e could be mitigated per year by 2050, through sustainable land management approaches such as increasing soil organic matter, erosion control, improved fertiliser management, improved crop management, improved manure management, higher quality feed, and use of varieties, breeds and genetic improvement.

Source: IPCC 2019

The IPCC also identifies the critical role of policymakers, highlighting that “many sustainable land management practices are not widely adopted due to insecure land tenure, lack of access to resources and agricultural advisory services, insufficient and unequal private and public incentives, and lack of knowledge and practical experience”.

This will require no small amounts of investment by developing economies. Part of the cost-benefit calculus will be the local impacts of unsustainable farm practices — fertiliser over-use is now clearly a climate problem, but has been polluting our groundwater, and exacerbating economic inequality for a while now.

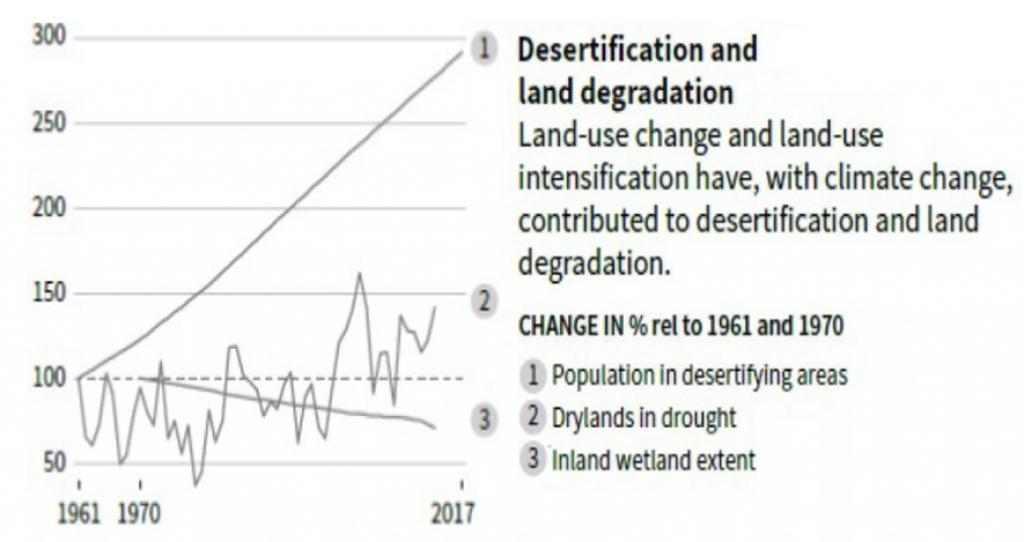

Finally, the IPCC also indicates better agriculture practices as a solution to the growing desertification crisis.

Source: IPCC 2019

It incentivises practices such as growing green manure crops and cover crops, crop residue retention, and reduced / zero tillage, by identifying their potential to mitigate climate change. The use of cover crops, for example, could sequester as much as 0.44 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide each year, even if applied over only a quarter of the world’s cropland.

While still modest relative to the energy sector, the importance of agriculture as a cause of climate change could grow in the coming years. Carbon is predominantly an energy sector problem, but agriculture contributes an estimated 56 per cent of non-carbon dioxide (ie methane and nitrous oxide) emissions.

These gases have a much higher global warming potential per unit than carbon dioxide. Estimates of their warming potential are still being revised upward. Agriculture is hence a sector ripe for climate action, even if it is not necessarily tagged as such.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.